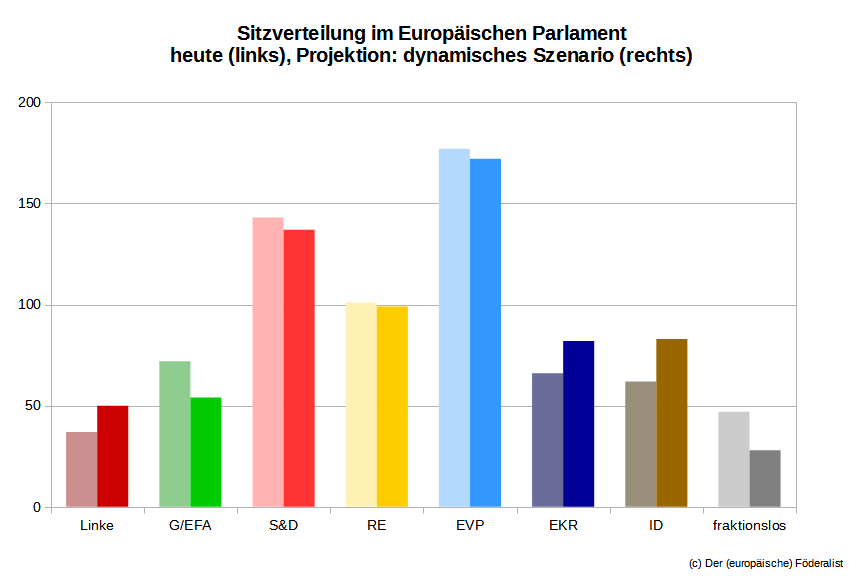

| Left | G/EFA | S&D | RE | EPP | ECR | ID | NI | other | |

| EP today | 37 | 72 | 143 | 101 | 177 | 66 | 62 | 47 | – |

| March 23 | 44 | 42 | 137 | 94 | 162 | 78 | 68 | 38 | 42 |

| May 23 | 49 | 50 | 137 | 92 | 162 | 79 | 67 | 33 | 36 |

| dynamic | 50 | 54 | 137 | 99 | 172 | 82 | 83 | 28 | – |

The European elections are approaching – and with them the first pre-election skirmishes. In early May, Iratxe García Pérez (PSOE/PES), leader of the centre-left S&D group in the European Parliament, declared that cooperation with the centre-right EPP was “no longer possible”. Frans Timmermans (PvdA/PES), Commission Vice-President and Socialist lead candidate in 2019, recently doubled down, speaking of a “new political dynamic” in which the EPP was no longer “willing to compromise”. EPP spokesperson Pedro López de Pablo (PP/EPP) countered that the EPP would of course continue to work with the S&D and that it was rather García Pérez herself who had “authority problems” within her own group.

The background to this dispute is a shift to the right by the EPP in recent months. Its leader, Manfred Weber (CSU/EPP), has not only conspicuously sought the proximity of the Italian head of government, Giorgia Meloni (FdI/ECR). The EPP is also trying to distinguish itself on substantive matters by attacking the EU’s climate policy. Speculation about a new centre-right parliamentary majority – consisting of the EPP, the right-wing ECR and the liberal RE group, and excluding the Social Democrats – has not abated. And the fact that Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis (ND/EPP), a key internal EPP supporter of Weber’s right-wing course, won a surprisingly large victory in last weekend’s national elections is likely to further fuel the debate.

In short, the climate in the European Parliament is getting rougher. Is the “permanent grand coalition” of EPP, S&D and RE, which has always been at the centre of majority building in the European Parliament, coming to an end?

Polarisation as a campaign ritual

If you think back a little, however, you will quickly remember that the S&D had already proclaimed the “end of the grand coalition” in 2016, with little practicle effect. EU politics is structurally based on consensus: Majorities in the European Parliament that exclude one of the major parties are possible for specific votes, but not sustainable in the long term. It is therefore already clear that cooperation between the EPP, S&D and RE will continue also after the 2024 European election. The alternative would be a blockade of the Parliament, which would benefit no one.

But it is difficult to run a campaign on such a premise. In order to make voters aware of the differences between the parties, a certain degree of polarisation is needed, and so it is part of the European political ritual for the EPP and the S&D to publicly declare their deep mutual dislike before a European election.

What will be interesting to see, however, is how quickly the parties can come together again after the election – when they will have to agree, for example, on a Commission President or a legislative programme for the next years. In the institutional battle over the lead candidate procedure, a divided Parliament will be easy prey for the European Council.

Committed to the lead candidatesBut that is still a long way off. Before the leading candidates can compete for the Commission presidency, the European parties must first decide on nominating them. One year before the election, Manfred Weber for the EPP, the leader of the European Left, Walter Baier (KPÖ/EL), and the European Greens have all publicly committed themselves to the leading candidates system, and the European Socialists are also certain to put forward a candidate. However, it is not until the summer or even later in the year that the parties will decide on how exactly they will nominate their candidates.

Meanwhile, the two European right-wing parties, ID and ECR, are unlikely to put forward leading candidates in 2024. And also among the Liberals, things are still unclear: Commission Vice-President Margrete Vestager (RV/ALDE), the most visible member of the seven-strong liberal top team in 2019, recently expressed “personal reservations” about the procedure.

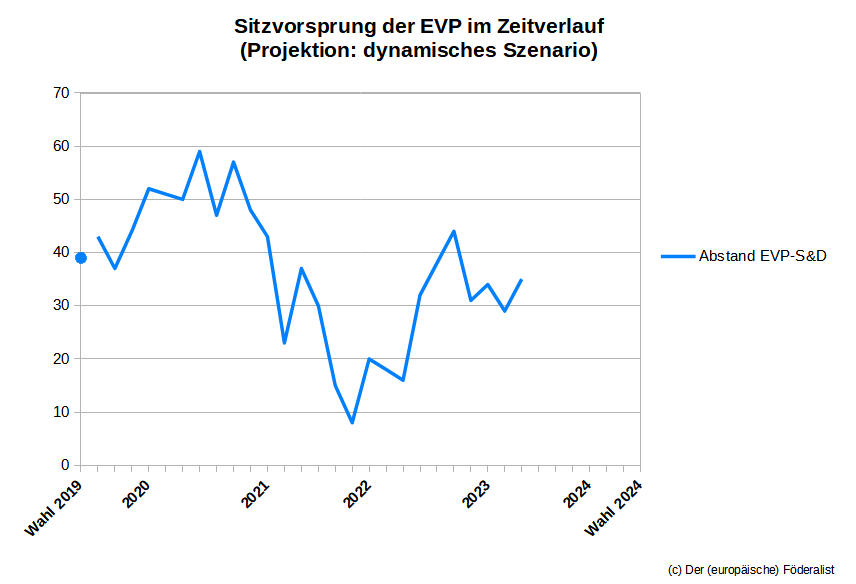

However, the Liberals are unlikely to play a central role in the selection of the Commission president anyway. The only groups with a realistic chance of winning the election are the EPP and the S&D. In the last weeks, the race between them has barely moved: In the baseline scenario of the current seat projection, both groups have exactly the same number of seats as in the last projection at the end of March.

This plays into the hands of the EPP, whose lead over the Social Democrats is somewhat smaller than in the last election in 2019, but still offers a reasonably comfortable cushion. But of course nothing is decided yet, and the S&D still has an entire year to close the gap.

EPP scores points in Greece …

In detail, the latest poll results of the two main political groups vary considerably from one member state to another. The EPP is gaining ground in Greece, but also in Germany and France. In Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia, small EPP member parties are once again just above the threshold for entering Parliament.

Elsewhere, however, things are going less smoothly for the centre-right: In Spain, Portugal, Sweden, Poland, the Czech Republic and Croatia, EPP member parties fall slightly behind in the projection – although in most cases this is only due to small fluctuations in the polls. Overall, the EPP group remains at 162 seats (±0 compared to March).

… and S&D in Italy

The Social Democrats, on the other hand, can take heart in particular from Italy, where the PD has made steady gains since electing the charismatic left-wing activist Elly Schlein as its new leader in February. In Sweden and Greece, the Social Democrats are gaining some ground, too.

In Germany, Spain, Portugal and Austria, however, the S&D member parties suffered losses in the latest polls. On balance, the S&D projection is unchanged from March (137 seats/±0).

Liberals fall back

The RE group is performing somewhat weaker than eight weeks ago. In both Germany and France, the Liberals went through a crisis in the spring from which they are slowly recovering. In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, too, RE member parties are doing slightly better than in March.

In other countries, however, the situation is considerably worse: In Italy, the liberal-centrist alliance between Azione (EDP) and Italia Viva (EDP) ended with mutual personal accusations between the two party leaders. In Finland, Keskusta (ALDE) suffered a crushing defeat in the national parliamentary election in April and has fallen further behind in the polls since. In the Netherlands, the liberal-conservative governing party VVD (ALDE) has been hit by the rapid rise of the agrarian-populist BBB (–). Overall, the RE group falls back to 92 seats (–2) in the seat projection – its worst performance since summer 2020.

Greens make strong gains

Meanwhile, the parties on the left of the political spectrum are making significant gains. Although the Greens are in crisis in their main stronghold Germany, several other member parties of the Greens/EFA group have recently improved their standing in the polls. These include the French EELV (EGP), the Czech Piráti (PPEU) and the Swedish MP (EGP), which is now back above the national four per cent threshold. Moreover, the Luxembourg Piratepartei and the Dutch Volt party would enter parliament for the first time.

All in all, this brings the projection for the Greens/EFA group to 50 seats (+8), its best figure in two years. For the European Greens, who suffered one setback after another in the polls during the first half of the parliamentary term, things seem to be moving forward again.

Left makes up for spring losses

Also the Left makes significant gains in the seat projection, making up for much of the losses it suffered in the polls in spring. Although its Greek affiliate Syriza fell short of expectations in the recent national parliamentary election, this is more than offset by gains for the Left parties in France, Belgium and Portugal. The Austrian KPÖ, which has recently enjoyed an unusual surge in the polls, is also included in the table for the first time. All in all, the Left group rises to 49 seats (+5) in the projection, which is roughly in line with its long-term average during this election period.

Finally, both the Greens/EFA and the Left have also been affected by a change in the Spanish party system: In early April, the left-wing IU party, which had previously cooperated closely with Podemos, joined forces with several Green or Green-aligned parties to form a new alliance called Sumar. While it is quite possible that Podemos will also join this alliance in the end, for the time being the seat projection assumes that there will be two separate lists and that the Sumar MPs will split between the Left group and the Greens/EFA.

ECR outpaces ID

On the right of the political spectrum, there has been less movement in the polls recently. Who did move, however, was one party: The Finnish PS announced in early April, shortly after their success in the national election, that they would return from the ID to the ECR group. The obvious aim of this move is to “normalise” the PS in terms of European policy. As the party wants to participate in the next Finnish government coalition, it prefers to surround itself with government parties like Italy’s FdI and Poland’s PiS rather than permanent opposition parties like France’s RN and Germany’s AfD.

At the same time, the PS group change is emblematic of a power shift within the European Right: While the ID attracted a lot of public attention a few years ago, the ECR has gradually overtaken it as the stronger, more visible and more influential group. In the seat projection, however, the ECR can only make small gains despite its new member from Finland. Slight downward fluctuations in the – generally quite volatile – polls from Romania and the Czech Republic keep the group at 79 seats (+1). The ID, on the other hand, gains ground in Germany and Estonia and remains at 67 seats (–1) despite the departure of the PS.

Losses for “other” and non-attached partiesThe non-attached parties fared worse than in March. This is mainly due to the French right-wing populist party Reconquête, which fell below the national five per cent threshold in the latest polls. The Slovak far-right party Republika, which had made gains in the spring, is also falling back. All in all, the non-attached parties stand at 33 seats (–5) now.

The “other” parties, which are currently not represented in the European Parliament and also don’t belong to any European party, come to 36 seats (–6). Among others, the French centre-left alliance PRG/FGR, the Greek left-wing party MeRA25 as well as the Hungarian satirical party MKKP would no longer win a seat in the Parliament according to the latest polls. On the other hand, the Dutch agrarian-populist BBB continues to make significant gains and now leads the national polls by a wide margin. It is still unclear which group the party will join after the European election. But the fact that the EPP has in recent weeks taken up the fight of conservative farmers against ambitious climate and environmental protection is likely to be viewed with favour by the BBB.

The overview

The following table breaks down the distribution of seats in the projection by individual national parties. The table follows the baseline scenario, in which each national party is attributed to its current parliamentary group (or to the parliamentary group of their European political party) and parties without a clear attribution are labelled as “other”.

In contrast, the dynamic scenario of the seat projection assigns each “other” party to the parliamentary group to which it is politically closest, and also takes into account other possible future group changes of individual national parties. In the table, the changes in the dynamic scenario compared to the baseline scenario are indicated by a coloured font and a mouseover text.

In the absence of pan-European election polls, the projection is based on an aggregation of national polls and election results from all member states. The specific data basis for each country is explained in the small print below the table. For more information on European parties and political groups in the European Parliament, click here.

New national seat quotas

And another technical note: Before the European election, the member states’ national seat quotas are redefined. According to Art. 14 (2) TEU, this must be done according to the principle of “degressive proportionality” – large states get more seats than small ones, but small states get more seats per inhabitant than large ones. As the number of inhabitants of the countries changes, the seat quotas have to be adjusted before each election.

There is no set formula for this, however. Instead, the European Council (on the initiative and with the consent of the European Parliament) must take a unanimous decision on the distribution of seats. This Wednesday, the Parliament’s constitutional committee was going to table a proposal in this regard, which would give some countries additional seats and increase the overall size of the Parliament. However, the committee has not yet reached a conclusion, and the final decision rests with the heads of state and government anyway. Provisionally, the seat projection is therefore still based on the old distribution of 705 seats.

| Left | G/EFA | S&D | RE | EPP | ECR | ID | NI | other | |

| EP today | 37 | 72 | 143 | 101 | 177 | 66 | 62 | 47 | – |

| March 23 | 44 | 42 | 137 | 94 | 162 | 78 | 68 | 38 | 42 |

| May 23 | 49 | 50 | 137 | 92 | 162 | 79 | 67 | 33 | 36 |

| dynamic | 50 | 54 | 137 | 99 | 172 | 82 | 83 | 28 | – |

| Left | G/EFA | S&D | RE | EPP | ECR | ID | NI | other | |

| DE | 5 Linke | 15 Grüne 1 Piraten 1 ÖDP 1 Volt |

17 SPD | 7 FDP 2 FW |

28 Union 1 Familie |

15 AfD | 2 Partei | 1 Tier | |

| FR | 10 LFI | 8 EELV | 6 PS | 21 Ens | 11 LR | 23 RN | |||

| IT | 18 PD | 4 Azione | 7 FI 1 SVP |

25 FdI | 8 Lega | 14 M5S | |||

| ES | 3 Podemos 3 Sumar 1 Bildu |

2 Sumar 2 ERC |

17 PSOE | 1 Cʼs 1 PNV |

19 PP | 9 Vox | 1 JxC | ||

| PL | 5 Lewica | 4 PL2050 |

15 KO 3 KP |

20 PiS | 5 Konf | ||||

| RO | 13 PSD | 3 USR | 8 PNL 2 UDMR 1 PMP |

6 AUR | |||||

| NL | 2 PvdD 1 SP |

3 GL 1 Volt |

2 PvdA | 4 VVD 2 D66 |

1 CDA 1 CU |

1 JA21 |

2 PVV | 9 BBB | |

| EL | 5 Syriza | 3 PASOK | 10 ND | 1 EL | 2 KKE | ||||

| BE | 3 PTB | 1 Groen 1 Ecolo |

2 Vooruit 2 PS |

1 O-VLD 2 MR |

1 CD&V 1 LE 1 CSP |

3 N-VA | 3 VB | ||

| PT | 2 BE 1 CDU |

6 PS | 2 IL | 6 PSD | 4 CH | ||||

| CZ | 3 Piráti |

10 ANO | 1 STAN |

4 ODS | 3 SPD | ||||

| HU | 5 DK |

1 MM | 1 KDNP | 12 Fidesz |

2 MHM |

||||

| SE | 2 V | 1 MP | 9 S | 1 C |

4 M |

4 SD | |||

| AT | 1 KPÖ | 2 Grüne | 4 SPÖ | 2 Neos | 4 ÖVP | 6 FPÖ | |||

| BG | 2 BSP | 3 DPS | 5 GERB |

4 PP-DB 3 V |

|||||

| DK | 1 Enhl. | 2 SF | 4 S | 2 V 2 LA 1 M |

1 K | 1 DD |

|||

| FI | 1 Vas | 1 Vihreät | 3 SDP | 1 Kesk | 4 Kok | 4 PS | |||

| SK | 3 Hlas-SD 3 Smer-SSD |

2 PS | 1 D 1 KDH 1 OĽANO |

1 SaS | 1 SR | 1 REP | |||

| IE | 6 SF | 3 FF | 4 FG | ||||||

| HR | 3 SDP | 5 HDZ | 2 Možemo 1 Most 1 DP |

||||||

| LT | 2 LVŽS | 3 LSDP | 1 LRLS |

2 TS-LKD | 1 DP | 2 DSVL |

|||

| LV | 1 Prog |

2 JV |

1 NA | 2 ZZS 1 LRA 1 S! |

|||||

| SI | 1 SD | 3 GS | 3 SDS 1 N.Si |

||||||

| EE | 2 RE 2 KE |

2 EKRE | 1 E200 | ||||||

| CY | 2 AKEL | 1 EDEK 1 DIKO |

2 DISY | ||||||

| LU | 1 Gréng 1 PPLU |

1 LSAP | 1 DP | 2 CSV | |||||

| MT | 3 PL | 3 PN |

| Left | G/EFA | S&D | RE | EPP | ECR | ID | NI | other | |

| 22/05/2023 | 49 | 50 | 137 | 92 | 162 | 79 | 67 | 33 | 36 |

| 27/03/2023 | 44 | 42 | 137 | 94 | 162 | 78 | 68 | 38 | 42 |

| 01/02/2023 | 50 | 42 | 135 | 96 | 168 | 78 | 65 | 37 | 34 |

| 06/12/2022 | 51 | 44 | 136 | 93 | 166 | 79 | 64 | 37 | 35 |

| 12/10/2022 | 52 | 42 | 127 | 100 | 169 | 79 | 63 | 35 | 38 |

| 20/08/2022 | 52 | 47 | 134 | 98 | 170 | 75 | 63 | 27 | 39 |

| 22/06/2022 | 54 | 44 | 133 | 101 | 165 | 77 | 64 | 31 | 36 |

| 25/04/2022 | 59 | 39 | 139 | 97 | 157 | 78 | 64 | 38 | 34 |

| 01/03/2022 | 53 | 36 | 139 | 98 | 158 | 78 | 62 | 45 | 36 |

| 04/01/2022 | 51 | 39 | 142 | 99 | 165 | 73 | 62 | 34 | 40 |

| 08/11/2021 | 50 | 42 | 144 | 96 | 155 | 75 | 72 | 36 | 35 |

| 13/09/2021 | 54 | 42 | 141 | 98 | 160 | 70 | 75 | 33 | 32 |

| 21/07/2021 | 52 | 45 | 133 | 97 | 167 | 71 | 74 | 31 | 35 |

| 24/05/2021 | 50 | 50 | 125 | 95 | 167 | 74 | 73 | 33 | 38 |

| 29/03/2021 | 52 | 46 | 136 | 96 | 164 | 71 | 73 | 34 | 33 |

| 02/02/2021 | 52 | 45 | 135 | 94 | 184 | 70 | 71 | 21 | 33 |

| 09/12/2020 | 52 | 47 | 136 | 93 | 188 | 67 | 73 | 20 | 29 |

| 12/10/2020 | 51 | 49 | 127 | 96 | 193 | 67 | 71 | 21 | 30 |

| 14/08/2020 | 50 | 53 | 145 | 88 | 196 | 65 | 64 | 20 | 24 |

| 25/06/2020 | 48 | 55 | 143 | 91 | 203 | 64 | 63 | 20 | 18 |

| 26/04/2020 | 47 | 53 | 151 | 88 | 202 | 66 | 66 | 19 | 13 |

| 10/03/2020 | 51 | 58 | 138 | 88 | 188 | 67 | 82 | 21 | 12 |

| 09/01/2020 | 49 | 58 | 135 | 93 | 186 | 65 | 82 | 24 | 13 |

| 23/11/2019 | 48 | 57 | 138 | 99 | 181 | 62 | 82 | 22 | 16 |

| 23/09/2019 | 49 | 61 | 139 | 108 | 175 | 56 | 82 | 24 | 11 |

| 30/07/2019 | 47 | 64 | 138 | 108 | 180 | 57 | 82 | 22 | 7 |

| EP 2019 | 40 | 68 | 148 | 97 | 187 | 62 | 76 | 27 | – |

The “EP 2019” line indicates the distribution of seats as of July 2, 2019, when the European Parliament was constituted following the election in May 2019.

The table shows the values of the baseline scenario without the United Kingdom. An overview of the values including the United Kingdom for the period up to January 2020 can be found here. An overview of older projections from the 2014-2019 electoral period is here.

For countries where there are no specific European election polls or where the last such poll was taken more than a fortnight ago, the most recent poll available for the national parliamentary election or the average of all polls for the national or European Parliament from the two weeks preceding the most recent poll available is used instead. For countries where there are no recent polls for parliamentary elections, polls for presidential elections may be used instead, with the presidential candidates’ polling figures assigned to their respective parties (this concerns France and Cyprus in particular). For member states for which no recent polls can be found at all, the results of the last national or European elections are used.

As a rule, the national poll results of the parties are directly converted to the total number of seats in the country. For countries where the election is held in regional constituencies without proportional representation (currently Belgium and Ireland), regional polling data is used where available. Where this is not the case, the number of seats is still calculated for each constituency individually, but using the overall national polling data in each case. National electoral thresholds are taken into account in the projection where they exist.

In Belgium, constituencies in the European election correspond to language communities, while polls are usually conducted at the regional level. The projection uses polling data from Wallonia for the French-speaking community and polling data from Flanders for the Dutch-speaking community. For the German-speaking community, it uses the result of the last European election (1 seat for CSP).

In countries where it is common for several parties to run as an electoral alliance on a common list, the projection makes a plausibility assumption about the composition of these lists. In the table, such multi-party lists are usually grouped under the name of the electoral alliance or of its best-known member party. Sometimes, however, the parties of an electoral alliance split up after the election and join different political groups in the European Parliament. In this case, the parties are listed individually and a plausibility assumption is made about the exact distribution of seats on the joint list. This concerns the following parties: Italy: SI (place 1 and 3 on the list) and EV (2, 4); Spain: ERC (1, 3-4), Bildu (2) and BNG (5); PNV (1) and CC (2); Poland: PL2050 (1, 3, 5 etc.), KP (2, 4, 6 etc.); Netherlands: CU (1, 3-4) and SGP (2, 5); Hungary: Fidesz (1-6, from 8) and KDNP (7); Slovakia: PS (1) and D (2). Moreover, it is assumed that the members of the Spanish political alliance Sumar will be divided 50/50 between the Left and the Greens/EFA groups.

In France, several centre-left parties (LFI, PS, EELV, PCF) have joined forces to form the electoral alliance NUPES for the 2022 national parliamentary election. However, it is unlikely that this alliance will last in the next European election. In the projection, therefore, the poll ratings or electoral results of the alliance are divided among the individual parties according to the ratio of the average poll ratings of the parties in the most recent polls that showed them individually.

Since there is no electoral threshold for European elections in Germany, parties can win a seat in the European Parliament with less than 1 per cent of the vote. Since German polling institutes do not usually report values for very small parties, the projection includes them based on their results at the last European election (2 seats each for PARTEI and FW, 1 seat each for Tierschutzpartei, ödp, Piraten, Volt and Familienpartei). Only if a small party achieves a better value in current polls than in the last European election, the poll rating is used instead.

In Italy, a special rule makes it easier for minority parties to enter the European Parliament. In the projection, the Südtiroler Volkspartei is therefore always listed with its result at the last European election (1 seat).

Germany: national polls, 11-20/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

France: national polls, 5/4/2023, source: Wikipedia; for the distribution among the member parties of the electoral alliance NUPES: national polls, 21/3/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Italy: national polls, 4-18/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Spain: national polls, 9-21/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Poland: national polls, 12-19/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Romania: national polls, 20/3/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Netherlands: national polls, 20/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Greece: results of the national parliamentary election, 21/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Belgium; Dutch-speaking community: regional polls (Flanders) for the national parliamentary election, 23-27/3/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Belgium; French-speaking community: regional polls (Wallonia) for the national parliamentary election, 27/3/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Belgien, German-speaking community: result of the European election, 26/5/2019.

Portugal: national polls, 5/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Czech Republic: national polls, 26/4-5/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Hungary: national polls, 28/4-5/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Sweden: national polls, 30/4-10/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Austria: national polls, 26-27/4/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Bulgaria: national polls, 5/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Denkmark: national polls, 21/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Finland: national polls, 2-12/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Slovakia: national polls, 10/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Ireland: national polls, 6-9/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Croatia: national polls, 25/4-7/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Lithuania: national polls, 22/4-5/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Latvia: national polls, April 2023, source: Wikipedia.

Slovenia: national polls, 4/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Estonia: national polls, 15/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Cyprus: first round results of the national presidency election, 5/2/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Luxembourg: national polls, 6/4/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Malta: national polls, 19/5/2023, source: Wikipedia.

Correction notice: An earlier version of this article stated that the constitutional committee of the European Parliament had already tabled a proposal for the reallocation of national seat quotas after the 2024 election, on which the European Council would now have to take a decision. In fact, however, the corresponding decision in the committee was postponed.