Mit:

- Carmen Descamps, Bundesverband der Energie- und Wasserwirtschaft, Brüssel

- Manuel Müller, Finnish Institute of International Affairs / Der (europäische) Föderalist, Helsinki

- Julian Plottka, Universität Passau / Universität Bonn

- Sophie Pornschlegel, Cadmus Europe / Ifok, Brüssel

Dieses Gespräch entstand als Online-Chat und wurde redaktionell bearbeitet.

- Nur noch 366 Mal schlafen, dann ist wieder Europawahl!

Manuel

Der Countdown läuft: Wenn dieses Quartett erscheint, ist es noch genau ein Jahr bis zur Europawahl am 6.-9. Juni 2024. Die letzten Umfragen sehen einen knappen, aber stabilen Vorsprung der Europäischen Volkspartei vor der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Europas, Verluste für die Grünen, wenig Veränderung für die Liberalen und Zugewinne am linken und rechten Rand. Die europäischen Parteien wollen in den nächsten Wochen festlegen, wie (und ob) sie ihre Spitzenkandidat:innen nominieren werden. Und auch die ersten Wahlkampfscharmützel sind schon zu erkennen, etwa wenn die Chefin der S&D-Fraktion ankündigt, mit der EVP sei keine Zusammenarbeit mehr möglich.

Wie geht es euch: Seid ihr schon gespannt auf die Europawahl?

Erstarken der Extreme

Carmen

Gespannt natürlich, das steht außer Frage – für EU-Nerds ist das doch das Ereignis alle fünf Jahre. Zur Spannung und Vorfreude mischt sich bei mir aber auch immer mehr Realismus. Ich hoffe auf strategische Inhalte, eine zukunftsgerichtete Agenda der demokratischen Parteien und natürlich insbesondere der EU-Kommission.

Personalien und prominente „Köpfe“ sind natürlich für die Identifikation wichtig, aber es sollte weniger um politische Grabenkämpfe und personelle Deals als um den ernsthaften Willen, als EU das gemeinsame Projekt und wichtige Dossiers voranzubringen, gehen. Das prognostizierte Erstarken der politischen Ränder trägt dazu nicht gerade bei. Gepaart mit niedriger Wahlbeteiligung könnte das noch für Überraschungen sorgen.

Julian

Ich bin leider gar nicht gespannt. Von den bewusst miterlebten Europawahlen habe ich noch von keiner so wenig erwartet. Ich weiß allerdings nicht, ob das noch eine Nachwehe des gescheiterten Spitzenkandidatenverfahrens von 2019 ist, der Eindruck des Kriegs in der Ukraine oder die Erwartung, dass angesichts der großen Mobilisierung beim letzten Mal die Wahrscheinlichkeit groß ist, dass die Wahlbeteiligung diesmal nicht weiter steigen wird. Einen Schub wie 2019 sehe ich diesmal leider nicht.

Sophie

Erst mal: Hallo zusammen, schön euch nach langer Quartett-Pause wieder zu sehen!

Ich bin auf die Europawahl sehr gespannt, vor allem weil es bis zur Wahl unklar bleiben wird, wie die Ergebnisse aussehen. Umfragen kann man heutzutage ja nicht unbedingt vertrauen. Gleichzeitig bin ich auch etwas besorgt, dass die Extremen Stimmen gewinnen werden, wodurch das Parlament geschwächt und die Europapolitik in eine wenig konstruktive Richtung gelenkt wird.

Gewöhnung an die Rechtsaußenparteien?

Julian

Ich habe das Gefühl, dass du mit dieser Sorge ziemlich alleine bist. 2019 gab es eine so große Angst vor einem Rechtsruck, dass selbst Unternehmen für die Europawahl mobilisiert haben. Ich erinnere mich an eine SayYesToEurope-Speziallackierung einer Lufthansa-Maschine und an eine Europawahl-Sonderausgabe der DB-Mobil. Mein Eindruck ist, diese Angst ist einem Fatalismus gewichen. Oder täusche ich mich?

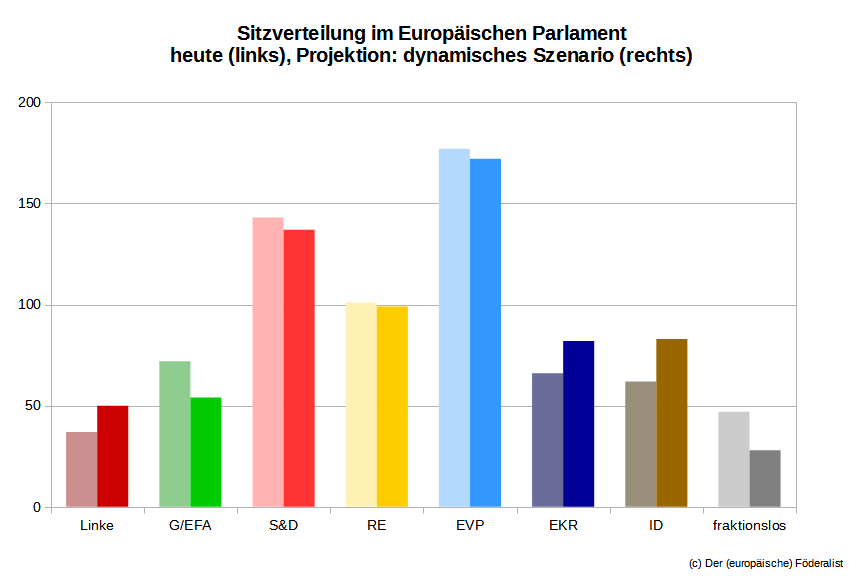

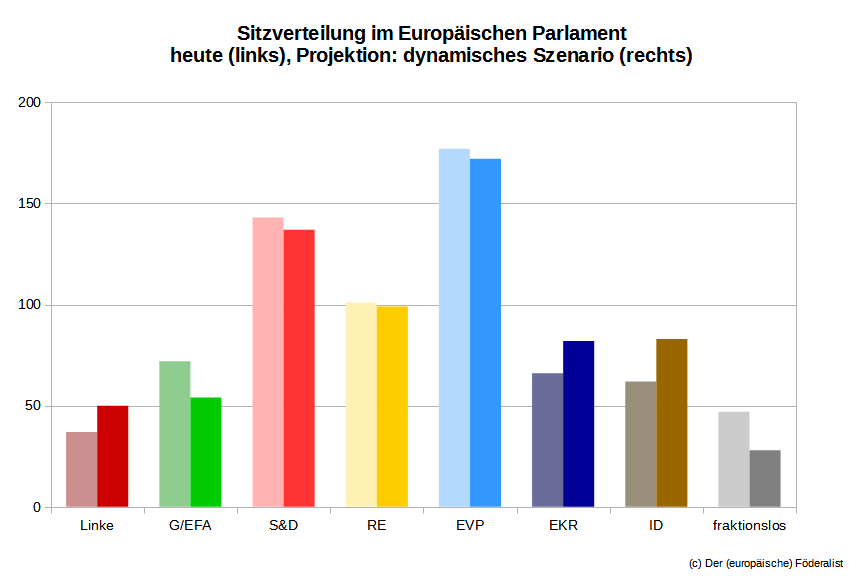

- Nach der Sitzprojektion gewinnen beide Rechtsaußenfraktionen Sitze dazu.

Manuel

Ich sehe das ähnlich. Klar ist, dass die europäischen Rechtsparteien in den letzten Jahren weiter gewachsen sind, in verschiedenen Ländern mitregieren und im Europäischen Parlament einen so großen Sitzanteil wie noch nie einnehmen könnten.

Aber als man sich bei den nationalen Wahlen 2017 in Frankreich und den Niederlanden vor einem Sieg der Rechten sorgte, löste das noch europaweite Wellen aus. In Deutschland zum Beispiel entstand als Reaktion darauf die Pulse-of-Europe-Bewegung, die dann auch die Stimmung im Europawahlkampf 2019 mitprägte. Als dann hingegen 2022 in Italien wirklich die Rechten gewannen, war die Reaktion darauf viel verhaltener. Offenbar hat inzwischen tatsächlich eine gewisse Gewöhnung eingesetzt.

Allerdings stimmt natürlich auch, dass die Rechten im Europäischen Parlament weiterhin weit von einer eigenen Mehrheit entfernt sein werden. Am Ende wird es ihnen auch nach 2024 leichter fallen, über die von ihnen kontrollierten Regierungen im Rat Einfluss auf die EU-Politik zu nehmen als über das Parlament, wo sie einfach überstimmt werden können.

Sophie

Ja, es stimmt, dass die Rechtsextremen inzwischen „normalisiert“ werden. Letztens saß ich in Brüssel in einer Veranstaltung mit Lobbyist:innen, in der davon die Rede war, dass die Fraktionen EKR und ID „konservativ“ seien. Ich habe mich gefragt, was dann eigentlich die EVP sein soll.

Aber Julian, es kommt darauf an, mit wem du sprichst: Die „EU-Nerds“, von denen Carmen gesprochen hat, wissen schon, dass mehr Macht für die extremistischen Parteien nichts Gutes für die Entscheidungsprozesse in Brüssel bedeutet. Es geht dabei vor allem auch um die Handlungsfähigkeit der EU. In der nächsten Legislaturperiode wird die EU weiterhin auf zahlreiche Krisen antworten müssen. Wenn sie das nicht schafft, werden die Populist:innen das noch weiter ausschlachten und es als Argument dafür nutzen, dass die Macht wieder von Brüssel zurück in die Hauptstädte sollte.

Carmen

Na, diesen Gedanken des „take back control“ kennen wir doch vom Brexit … Leider gibt es solche Rufe inzwischen nicht mehr nur von Politiker:innen populistischer oder extremer Parteien. Es scheint zunehmend salonfähig zu sein, eine europäische Desintegration bzw. Rückverlagerung von Kompetenzen zu fordern.

Julian

Schlimm ist, dass die Unterschiede zwischen Konservativen und Rechten auch von den echten Konservativen eingeebnet werden – in der falschen Hoffnung, dass man so den Aufstieg der Rechten bremsen könnte. Durch diese Anpassung haben die Rechten im Parlament dann doch wieder einen Einfluss, der weiter reicht als ihr Stimmengewicht.

Kommt das „Ende der Großen Koalition“?

Sophie

Auch in dieser Hinsicht wird der Europawahlkampf spannend: Wird die EVP sich als Brandmauer gegen die Rechtsextremen stellen oder nicht? Bisher sieht es eher nicht danach aus, aber am Ende wird es auch stark auf die Positionierung der CDU unter Friedrich Merz ankommen.

Manuel

Die EVP hat diese Debatte in letzter Zeit natürlich selbst ordentlich befeuert, indem etwa Manfred Weber oder Antonio Tajani immer wieder ihre Offenheit für eine Kooperation zumindest mit der EKR-Fraktion signalisiert haben. Die S&D (etwa in Person von Iratxe García Pérez oder Frans Timmermans) deutet deshalb seit einer Weile immer öfter an, dass die jahrzehntealte „informelle Große Koalition“ nach der Europawahl enden könnte, weil sich die EVP nicht mehr zur Mitte, sondern nach rechts orientiert.

Ich selbst halte das nicht für besonders realistisch. Zum einen ist die EU-Gesetzgebung allgemein so konsensorientiert, dass Mehrheiten ohne eine der großen Parteien allenfalls punktuell, aber nicht strukturell möglich sind. Zum anderen wäre in der aktuellen Situation für eine Mehrheit ohne die S&D jedenfalls die liberale Renew-Fraktion notwendig, die aber nicht systematisch mit der EKR wird zusammenarbeiten wollen. Was denkt ihr dazu?

Julian

Was ich aus der EVP wahrnehme, ist jedenfalls eine große Unzufriedenheit mit einer zu „linken“ oder zu „grünen“ Politik von der Leyens. Ich kann mir vorstellen, dass das parteiintern einer Öffnung nach rechts Vorschub leistet. Die Frage wird sein, ob eine kommende EVP-Kommissionspräsident:in ein konservativeres Profil entwickeln kann als die aktuelle, ohne mit der EKR zusammenzuarbeiten.

Stärkere Links-rechts-Gegensätze

Sophie

Ich kann mir schon vorstellen, dass es in der nächsten Legislaturperiode zu einer engeren Zusammenarbeit zwischen EVP und EKR kommt. Das würde bedeuten, dass die europäische politische Agenda sich stark nach rechts verschiebt – mit der Konsequenz, dass wir nirgendwo vorankommen, außer vielleicht bei der Beschneidung von Grund-, Menschen- und Minderheitenrechten.

Allerdings könnte das auch den Vorteil haben, dass es im Europäischen Parlament wieder eine stärkere Links-rechts-Unterscheidung gibt und die S&D eine stärker „linke“ Politik fahren könnte.

Julian

Das ist aber schon etwas zynisch – auf fünf Jahre rechte Politik zu hoffen, damit sich endlich wieder eine linke Opposition dagegen formieren kann. 🤨

Carmen

😲

Sophie

Na ja, es hängt weniger von den Rechtsextremen ab als von den Linken selbst, ob sie sich neu aufstellen. Den Democrats in den USA und der Labour Party in Großbritannien ist diese Neuaufstellung ja trotz Donald Trump und Boris Johnson nicht wirklich gelungen. Ich sage nur, dass es dadurch bei den Debatten im Europäischen Parlament vielleicht eine stärkere Links-rechts-Orientierung geben könnte, als es bisher der Fall ist.

Bleiben die Liberalen Königsmacher?

Carmen

Ich finde den Wunsch nach einer solchen Polarisierung sehr nachvollziehbar, aber mit Blick auf die derzeitige Stimmenverteilung nicht wirklich praktikabel, insbesondere politikfeldübergreifend. Mit wem sollte die S&D denn eine linke Mehrheit erreichen können – allein mit Grünen und Linken? Sehe ich nicht, und die Sitzprojektion auch nicht.

Spannend finde ich eher die Frage, ob die Liberalen – zwischen S&D und EVP – weiterhin die „Königsmacher“ bleiben werden. Oder ob, im Nachgang von Fridays for Future und Letzter Generation, die Grünen sie ablösen?

Sophie

Laut den Umfragen, die ich bisher gesehen habe, würden sowohl die Liberalen als auch die Grünen in den nächsten Europawahlen verlieren – wir dürfen da nicht von Deutschland auf die EU schließen.

Manuel

Nach der Projektion könnte es im nächsten Parlament zwei Gewichtsverschiebungen geben. Zum einen nach rechts: Bisher kommt ein Mitte-links-Bündnis aus S&D + Renew + Grünen + Linke ganz knapp auf eine absolute Mehrheit im Parlament, künftig wäre es recht weit davon entfernt. Umgekehrt hat ein Mitte-rechts-Bündnis aus EVP + Renew + EKR derzeit keine Mehrheit, künftig wäre es wenigstens nahe dran.

Die andere Gewichtsverschiebung ist von den Grünen zu den Liberalen: EVP und S&D haben seit 2019 zu zweit keine Mehrheit mehr, können sich aber aussuchen, ob sie ein Dreierbündnis mit Renew oder den Grünen bilden. Nach der Projektion wird es für EVP + S&D + Grüne hingegen eng – womit Renew in seiner Rolle als unverzichtbare Scharnierpartei weiter gestärkt würde. Wenn die Umfragen sich bestätigen, wäre eine Mehrheit ohne die Liberalen künftig noch schwieriger zu bilden als jetzt.

Sophie

Wie schätzt ihr denn die Chance ein, dass es im nächsten Parlament überhaupt zu stabilen „Koalitionen“ kommen wird? Mit der großen Fragmentierung und den stärkeren Extremen wird das sicher nicht einfach.

Manuel

Das stimmt. Aber genau deshalb erwarte ich ja auch, dass sich am Ende wieder die großen Mitte-Fraktionen – EVP, S&D und Renew – zusammenfinden werden. Das ist schlicht die einfachste Form, im Europäischen Parlament eine Mehrheit zu bilden; die Option, zu der man greift, wenn alles andere in die Blockade führen könnte.

Neue Abgeordnete: Frischer Wind, weniger Erfahrung

Julian

Wichtig finde ich noch, dass bei der Europawahl 2019 der Anteil der gewählten Abgeordneten ohne politische Vorerfahrung extrem hoch war. Mehr als 60 Prozent der Mitglieder waren neu im Parlament und mussten erst einmal lernen, wie es überhaupt funktioniert. Das ist aus meiner Sicht einer der Gründe, warum das Parlament in der aktuellen Legislaturperiode so schwach ist.

Wenn beim nächsten Mal der Anteil der neuen Europaabgeordneten geringer sein wird, wäre meine Hoffnung, dass sich wieder stabilere Bündnisse bilden lassen, denen es gelingt, die Position des Europäischen Parlaments auch gegen die anderen EU-Organe durchzusetzen.

Carmen

Prognosen zufolge wird der Abgeordneten-Turnover allerdings auch bei den nächsten Europawahlen mit über 50% weiterhin absehbar hoch sein. Einerseits eine Chance für frischen Wind, andererseits eben auch viel verloren gehendes Wissen über die Praktiken im Europäischen Parlament und die Art, wie man dort am besten Mehrheiten bildet.

Die von Julian angesprochene schwächere Rolle des aktuellen Parlaments hängt aus meiner Sicht aber nicht nur damit zusammen, sondern auch viel mit dem Krisenmodus der letzten Jahre – erst die Pandemie, dann der russische Angriffskrieg –, und vielleicht auch mit der starken Kommissionspräsidentin Ursula von der Leyen. Viele Notfallmaßnahmen, gerade auch im Energiebereich, sind ja gewissermaßen am Parlament vorbei beschlossen worden, viel mehr als Ex-post-Kommunikation blieb der Bürgerkammer da leider nicht. Mich erinnert das stark an die Eurorettungsaktionen in der Finanzkrise, bei denen ja auch immer wieder das Demokratiedefizit bemängelt wurde.

Julian

Angesichts der hohen Zahl neuer Abgeordneter fände ich es aus wissenschaftlicher Sicht interessant zu untersuchen, welche Lernprozesse in der aktuellen Legislatur stattgefunden haben und inwieweit sich das Parlament dadurch verändert hat. Wenn es wirklich so kommt, wie Carmen sagt, dann wäre es spannend zu sehen, ob die Fraktionen im Umgang mit der Diskontinuität dazugelernt haben und diesmal besser dafür sorgen, dass Wissen und Praxis weitergegeben werden.

Wer wird Spitzenkandidat:in?

Manuel

Kommen wir noch mal auf den anstehenden Wahlkampf zurück – speziell auf das Spitzenkandidatenverfahren, das ja bald wieder in aller Munde sein wird. In einem europapolitischen Quartett von Februar 2022 haben Sophie, Julian und ich schon einmal munter darüber spekuliert, wer Kandidat:in werden könnte. Hier sind unsere Tipps von damals:

| Julian |

Sophie |

Manuel |

| Ursula von der Leyen |

Stéphane Séjourné |

Enrico Letta |

| Katarina Barley |

Viktor Orbán |

Alice Bah Kuhnke |

| Mark Rutte |

Sanna Marin |

Giorgia Meloni |

| Sebastian Kurz |

Valdis Dombrovskis |

Bas Eickhout |

Wie plausibel findet ihr diese Namen aus heutiger Sicht?

Sophie

Also, einige von unseren Tipps sind definitiv nicht schlecht – andere sind etwas daneben, auch weil es inzwischen in bestimmten Mitgliedsländern Wahlen gab, die die politische Landschaft verändert haben. Viktor Orbán wird in den nächsten Jahren definitiv ungarischer Premierminister bleiben, und Giorgia Meloni hat jetzt auch ein nationales Regierungsamt.

Von der Leyen als EVP-Spitzenkandidatin klingt allerdings sehr plausibel. Die Frage ist für mich eher, welche Parteien sich wirklich auf den Prozess einlassen. Bei der ALDE wurden ja bereits Vorbehalte geäußert.

Kandidiert von der Leyen für eine zweite Amtszeit?

Julian

Bei von der Leyen bleibe ich dabei, dass sie gute Chancen hat – auch wenn die Prognose ein bisschen langweilig ist. Ich hatte oben ja bereits angesprochen, dass die EVP mit ihrem inhaltlichen Profil hadert. Das hat auch mit den Versprechen zu tun, die sie 2019 anderen Parteien geben musste, um auch als Nicht-Spitzenkandidatin gewählt zu werden. Wenn sie nun als Spitzenkandidatin antritt, könnte sie dieses Problem für ihre zweite Amtszeit beheben, da sie leichter eine Mehrheit im Parlament bekäme und weniger Rücksicht auf die anderen Parteien nehmen müsste.

- Begegnen sich Sanna Marin und Ursula von der Leyen 2024 im Wahlkampf wieder?

Auch Sanna Marin halte ich weiterhin für einen guten Tipp von Sophie. Sie kann mit ihrem sicherheitspolitischen Profil genau da punkten, wo die Sozialdemokrat:innen traditionell schwächer sind: in den zentral- und osteuropäischen Ländern.

Aus dem umgekehrten Grund würde ich heute nicht mehr auf Katarina Barley tippen. Eine deutsche Sozialdemokratin ist in Zentral- und Osteuropa momentan schwer zu vermitteln, auch wenn die Bundesregierung den Diskurs zur Unterstützung der Ukraine langsam besser in den Griff zu bekommen scheint.

Carmen

👍

Von der Leyen halte ich auch für sehr wahrscheinlich, zumal der deutsche Koalitionsvertrag von Herbst 2021 der Ampelkoalition diese Möglichkeit ausdrücklich eröffnet. Darin heißt es: „Das Vorschlagsrecht für die Europäische Kommissarin oder den Europäischen Kommissar liegt bei Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen, sofern die Kommissionspräsidentin nicht aus Deutschland stammt.“ Und: „Wir unterstützen ein einheitliches europäisches Wahlrecht mit teils transnationalen Listen und einem verbindlichen Spitzenkandidatensystem.“ Heißt also: Eine Spitzenkandidatin von der Leyen ist möglich und hätte auch die Unterstützung der Bundesregierung.

Auffällig ist auch, dass die Kommissionspräsidentin und ihr Team sich in der jüngsten Vergangenheit gerade in Bezug auf die langfristige Energiepolitik – also die Antwort auf den russischen Angriffskrieg und den Weg zur Energiesicherheit – sehr hervorgetan haben. Insbesondere hat von der Leyen die medienwirksame Außenkommunikation einiger Energie- und Klimadossiers übernommen, die eigentlich beim Ersten Vizepräsidenten Frans Timmermans oder bei der Energiekommissarin Kadri Simson liegen würden. Offenbar ist es von der Leyen wichtig, mit diesen Zukunftsthemen sichtbar zu sein.

Manuel

Und welche Namen, auf die wir letztes Jahr nicht gekommen sind, würden euch heute noch einfallen?

Sophie

Roberta Metsola, die aktuelle Parlamentspräsidentin, könnte noch eine plausible Kandidatin für die EVP sein. (Und sicherlich besser als ein zweites Mal Manfred Weber, der mit den Rechtsextremen liebäugelt.)

Carmen

Margrethe Vestager, Exekutiv-Vizepräsidentin der EU-Kommission und Wettbewerbskommissarin – auch wenn sie sich jüngst gegen das Spitzenkandidaten-System ausgesprochen hat, weil es ein Widerspruch sei, gleichzeitig für einen Parlamentssitz und ein Kommissionsamt zu kandidieren. Ich teile ihre Argumentation nicht und hoffe weiterhin, sie als strickende Spitzenkandidatin zu sehen. 😉 Außerdem hat ihre politische Familie, die Europäischen Liberalen, bislang keine Entscheidung zu dem Thema getroffen, da es noch „zu früh“ dafür sei.

Ist das Spitzenkandidatenverfahren diesmal erfolgreich?

Manuel

Damit stellt sich natürlich noch die – schon tausendfach diskutierte – Frage, ob das Spitzenkandidatenverfahren diesmal wieder „erfolgreich“ sein wird (was auch immer das Kriterium für einen solchen Erfolg wäre). Wenn von der Leyen wieder antritt und die EVP stärkste Fraktion wird, scheint es mir naheliegend, dass sowohl der Europäische Rat als auch eine Parlamentsmehrheit eine zweite Amtszeit von ihr unterstützen würden.

Interessant könnte es aus meiner Sicht aber werden, wenn bei der Wahl doch noch die S&D stärkste Fraktion wird. Als eine Art Worst-Case-Szenario könnte ich mir vorstellen, dass der Europäische Rat dann trotzdem von der Leyen vorschlägt – immerhin kennen die Staats- und Regierungschef:innen sie schon und wissen, dass sie von ihr keine allzu großen Ambitionen zu befürchten haben. Das könnte dann dazu führen, dass die S&D auf ihrer Kandidat:in beharrt, während gleichzeitig die EVP von der Leyen unterstützt und darauf verweist, dass diese ja Spitzenkandidatin war und daher durch das Verfahren legitimiert ist. Ergebnis: Niemand hätte eine Mehrheit, und alle würden wieder darüber streiten, was das Spitzenkandidatenverfahren „eigentlich“ bedeutet.

Julian

Das erscheint mir aber nicht unbedingt ein Worst-Case-Szenario, sondern eher eine Wiederholung der Situation von 2014. Denn wenn die S&D ihre Spitzenkandidat:in durchsetzen will und die Grünen sich ebenfalls gegen von der Leyen stellen, mit wem würde die EVP sie dann wählen wollen? Eine Koalition aus EVP, Renew und Rechten wäre doppelt schwierig: Zum einen käme es dann zu einer Diskussion innerhalb der Liberalen, die die Mehrheit weiter spaltet. Und zum anderen dürften auch im Europäischen Rat einige Regierungschef:innen Probleme mit einer Kommission von Gnaden der Rechtsparteien haben.

Das wäre also die Chance für eine Blockade im Parlament gegen den Europäischen Rat. Im günstigsten Fall könnten es die Sozialdemokrat:innen sogar schaffen, einen Teil der EVP-Mitglieder gegen von der Leyen aufzubringen.

Eine denkbare Pattsituation

Carmen

Dann stünden wir aber vor einer Pattsituation, oder? Wäre damit das Spitzenkandidatensystem endgültig begraben, weil sich die Parteien nach all den Schwierigkeiten davon verabschieden und bei der Europawahl 2029 keine Kandidat:innen mehr aufstellen würden?

Dass der Europäische Rat die Spitzenkandidaten-Regeln in dem beschriebenen Szenario etwas freier auslegen und keine Rücksicht auf die Parlamentsmehrheit nehmen würde, halte ich jedenfalls nicht für so abwegig. Zumal die sozialdemokratisch geführten Regierungen in der EU in der Minderheit sind und die „Anti-von-der-Leyen-Fraktion“ im Europäischen Rat wenig Fürsprecher:innen finden würde. Als starker sozialdemokratischer Vertreter fällt mir da (neben dem deutschen Kanzler) vor allem der spanische Premierminister Pedro Sánchez ein, dessen Zukunft mit der Neuwahl am 23. Juli ungewiss ist.

Manuel

Eben. Eine Mitte-links-Allianz ohne die EVP hätte im Europäischen Rat kaum eine Mehrheit. Eine Mitte-rechts-Allianz aus EVP, EKR und Liberalen wäre dort hingegen durchaus denkbar, insbesondere falls Spanien im Juli noch an die EVP fällt.

Sophie

Das wäre ja was ganz Neues, Manuel, dass man sich über das Spitzenkandidatenverfahren streitet! 😉 (Wobei die Debatte 2019 vor allem in Deutschland so hitzig war; in anderen Ländern wurde das viel weniger diskutiert.)

In einem Punkt möchte ich dir widersprechen: Ich habe von der Leyen nicht als „ambitionslose“ Kommissionspräsidentin wahrgenommen. Ihr Programm 2019 war sehr ambitioniert, und trotz der Krisen gab es von der EU-Kommission viele Vorschläge im Bereich Digitalisierung und Klimaschutz. (Viele davon sind dann im Rat versandet bzw. von den Regierungen verwässert worden. Aber das ist eine andere Frage.) Außerdem hat von der Leyen mit NextGenerationEU und der Impfstoffbeschaffung in den Krisen ziemlich wichtige Entscheidungen getroffen, obwohl der Europäische Rat immer stark auf seine Macht pocht.

Worin ich dir aber jedenfalls zustimme: Mit von der Leyen sind die Chancen am größten, dass es bei der Europawahl 2024 ein Spitzenkandidaten-Verfahren gibt, das auch dazu führt, dass die Kandidatin zur Kommissionspräsidentin wird.

Welche Ereignisse werden die Wahl prägen?

Manuel

Zum Abschluss noch eine Blitzrunde mit kurzen Antworten: Jeder nennt ein besonderes Thema oder Ereignis in den nächsten Monaten, das die Europawahl prägen wird.

Julian

Ukraine.

Carmen

Blackout im Winter 2023/2024.

Manuel

Eine intensivierte öffentliche Debatte über Vertragsreformen und die anstehende EU-Erweiterung.

Der Bürohund

Neuwahlen in Deutschland.

Sophie

Die ungarische Ratspräsidentschaft direkt nach der Europawahl. Und die belgische Parlamentswahl, die zeitgleich mit der Europawahl stattfindet und bei der die beiden separatistischen flämischen Rechtsparteien N-VA und Vlaams Belang viele Stimmen gewinnen könnten. Zugespitzt formuliert: Was wird aus der EU, wenn Belgien als Land womöglich bald nicht mehr existiert?

Julian

Es gab ja schon einmal die Idee, die europäische Hauptstadt in ein nicht-staatliches Territorium zu verlegen … 😉

Sophie

Meinst du nach London?

Manuel

Na, wenn das passiert, wird die Europawahl 2024 jedenfalls noch lange in Erinnerung bleiben! 😅

Die Beiträge geben allein die persönliche Meinung der jeweiligen Autor:innen wieder.

Frühere Ausgaben des europapolitischen Quartetts sind hier zu finden.

Bilder: Europawahlzettel: European Parliament/Pietro Naj-Oleari [

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0], via

Flickr; Marin und von der Leyen: Laura Kotila, valtioneuvoston kanslia [

CC BY 2.0], via

Flickr; Porträt Carmen Descamps: Life Studio [alle Rechte vorbehalten]; Porträt Manuel Müller: Eeva Anundi / Finnish Institute of International Affairs [alle Rechte vorbehalten]; Porträts Julian Plottka, Sophie Pornschlegel: privat [alle Rechte vorbehalten].