- Jetzt noch ein bisschen Besinnlichkeit – in einem Jahr werden schon wieder Spitzenkandidat:innen nominiert!

Erinnern Sie sich noch? Vor etwas mehr als einem Jahr kündigten sowohl Kommissionspräsidentin Ursula von der Leyen (CDU/EVP) als auch Ratspräsident Charles Michel (MR/ALDE) ein Motto für das Jahr 2022 an. Für die Kommission sollte es das „Europäische Jahr der Jugend“ werden, für den Ratspräsidenten das „Jahr der europäischen Verteidigung“. Rückblickend scheint es, dass Michel dabei die bessere Prognose getroffen hat: Der russische Angriff auf die Ukraine rückte verteidigungspolitische Fragen auf schmerzhafte Weise in den Mittelpunkt der EU-Agenda.

Für 2023 hat die Kommission nun das „Europäische Jahr der Kompetenzen“ ausgerufen (womit vor allem Aus- und Weiterbildungsmaßnahmen gemeint sind), Ratspräsident Michel hat auf ein Jahresmotto verzichtet. Vielleicht ist es ja besser so.

Krieg in der Ukraine

Klar ist, dass der russische Krieg in der Ukraine die EU auch in den nächsten Monaten weiter beschäftigen wird, und zwar auf ganz unterschiedlichen Ebenen. Am offensichtlichsten ist dabei die Dimension der Militärhilfe und die Debatte über ein mögliches Ende des Krieges. Nach der anfänglich bemerkenswert geschlossenen Reaktion der EU auf den Kriegsausbruch kam es schon 2022 rasch zu internen Kontroversen: Während die „Falken“ (vor allem im Nordosten der EU) auf eine klare Niederlage Russlands in der Ukraine setzen, um das Putin-Regime von neuen Aggressionen abzuschrecken, sind die (meist westeuropäischen) „Tauben“ eher offen für ein rasches Kriegsende und ein Einfrieren des Konfliktes.

Je länger sich der Krieg hinzieht, desto stärker könnten diese innereuropäischen Gegensätze deutlich werden. Eine transnationale Strategiedebatte zu führen wird 2023 deshalb wichtiger denn je – auch um zu verhindern, dass die Auseinandersetzung ins Toxische eskaliert. Angesichts des großen öffentlichen Interesses sind dabei nicht nur Expert:innen und Entscheidungsträger:innen gefordert, sondern vor allem auch die Massenmedien.

Energiekrise, Inflation, Rezession

Und natürlich wird die EU auch für die indirekten Folgen des Krieges weiter Antworten finden müssen: In der Energiekrise gelang es den Mitgliedstaaten in den letzten Tagen immerhin, sich auf ein gemeinsames Maßnahmenpaket zu einigen, das unter anderem den gemeinsamen Ankauf von Gas und einen Gaspreisdeckel vorsieht.

Doch die enorm gestiegenen Energiepreise lassen die EU schon jetzt auf eine gefährliche Kombination aus Inflation und Rezession zusteuern. Die Europäische Zentralbank steht damit vor dem Dilemma, entweder den Preiserhöhungen freien Lauf zu lassen – oder durch Zinserhöhungen die Inflation einzudämmen, aber auch die Wirtschaft noch weiter abzuwürgen.

Revision des mehrjährigen Finanzrahmens und der Defizitregeln

Vor diesem Hintergrund gewinnt auch die anstehende Halbzeitrevision des mehrjährigen Finanzrahmens der EU besondere Bedeutung. In der ersten Jahreshälfte 2023 will die Kommission dafür einen Vorschlag vorlegen. Schon jetzt hat das Europäische Parlament deutlich gemacht, dass es großen Überarbeitungsbedarf sieht: Weder Größe noch Struktur des jetzigen Finanzrahmens seien geeignet, um den vielen aktuellen Krisen entgegenzutreten. Außerdem will die Kommission im zweiten Halbjahr einen Vorschlag zu neuen Eigenmittelquellen vorlegen. Aber in beiden Fragen gilt im Rat (wie immer, wenn es in der EU um viel Geld geht) das Einstimmigkeitsprinzip. Und so werden wir auch diesmal wieder die Rituale einer Vetokratie mit ihren langen, zähen, unergiebigen Streitigkeiten erleben.

Und nicht nur über den EU-Haushalt, auch über die nationalen Haushalte und ihre Schulden wird die EU in den nächsten Monaten diskutieren. Im November hat die Kommission Vorschläge für eine Reform der Defizitregeln vorgelegt. Auf einen einfachen Nenner gebracht, ist die Idee dieser Reform, dass die Mitgliedstaaten mehr Spielräume zur Kreditaufnahme erhalten sollen – aber nur im Rahmen von individuellen, mit der Kommission abzuschließenden Vereinbarungen. Mehr schuldenpolitische Flexibilität, aber nur zu Zwecken, die auch die EU gutheißt: Statt eines starren Rahmens würden die Defizitregeln damit zu einem Instrument indirekter makroökonomischer Steuerung. Man darf gespannt sein, wieweit sich die Mitgliedstaaten darauf einlassen.

Debatten über Erweiterung …

Eine weitere Folge des Krieges in der Ukraine ist die wuchtige Rückkehr der EU-Erweiterungsdebatte. Nach dem kroatischen Beitritt 2013 hatte in der EU eine gewisse Erweiterungsmüdigkeit eingesetzt, jahrelang wurden die Staaten des westlichen Balkans mit politischen Spielchen auf Armeslänge gehalten – zum wachsenden Frust der dortigen Bevölkerung.

2022 jedoch brachte die veränderte geopolitische Lage eine neue Dynamik: In der Ukraine hat der Krieg nicht nur zu einer Stärkung der nationalen, sondern auch der europäischen Identität geführt. Nur wenige Tage nach Kriegsausbruch stellte die Selenskyj-Regierung einen EU-Beitrittsantrag, den die EU im Sommer mit der Verleihung des Kandidatenstatus beantwortete. Auch die Republik Moldau, Georgien, Nordmazedonien, Albanien, Bosnien-Herzegowina und Kosovo machten in den letzten Monaten Fortschritte auf ihrem Weg in die Union.

Entsprechend groß sind nun die Erwartungen in den Kandidatenländern, und die EU wird es sich kaum leisten können, diese wieder so zu enttäuschen wie in den letzten Jahren. Wie ernst es ihr mit der erweiterungspolitischen Zeitenwende wirklich ist, werden aber erst die nächsten Monate und Jahre zeigen, wenn aus symbolträchtigen Erklärungen konkrete Verhandlungen werden.

… und Vertiefung

Das vielleicht größte Hindernis für künftige Beitritte liegt dabei allerdings gar nicht bei den Kandidatenländern, sondern der EU selbst. Deren innere Verfahren funktionieren schon mit 27 Mitgliedstaaten oft mehr schlecht als recht, wie die „Permakrise“ der letzten zehn Jahre gezeigt hat.

Ob es um die Eurorettung, um die Migrationskrise, die Corona-Pandemie oder die Wahrung der Rechtsstaatlichkeit in den Mitgliedstaaten geht: Immer wieder handelte die EU zu spät oder zu schwach, ließ sich von einzelnen Mitgliedstaaten erpressen, musste verfassungsrechtliche Ausnahmeklauseln und Ad-hoc-Konstruktionen nutzen, traf wichtige Schlüsselentscheidungen ohne das gewählte Parlament und ließ es allgemein an klaren Verantwortlichkeiten vermissen.

All das würde sich nur noch weiter verschlimmern, wenn die Zahl der nationalen Vetoplayer von 27 auf 30 oder 35 steigt. Vor der Erweiterung muss also eine institutionelle Reform stehen, bei der es insbesondere um den Übergang von Einstimmigkeits- zu Mehrheitsentscheidungen gehen muss, aber auch um eine Stärkung der supranationalen Institutionen, klarere Kompetenzen und ein neues Wahlrecht.

Von der Zukunftskonferenz zum Konvent?

Und tatsächlich liegt ein solcher Reformkatalog ja bereits seit über einem halben Jahr vor: Am 9. Mai 2022 verabschiedete die EU-Zukunftskonferenz ihren Abschlussbericht, dessen Demokratie-Kapitel etliche weitreichende Vorschläge enthält, die nur durch eine Vertragsreform umzusetzen sein werden. Das Europäische Parlament forderte deshalb gleich nach der Konferenz die Einberufung des dafür notwendigen Konvents. Der Europäische Rat ging darauf jedoch erst einmal überhaupt nicht ein.

Der Grund dafür ist die fehlende Einigkeit unter den Regierungen, von denen mehrere die Idee einer Vertragsänderung sehr skeptisch sehen. Auch Schweden, das im ersten Halbjahr 2023 die Ratspräsidentschaft übernimmt, zählt nicht zu den Konventsbefürwortern. In ihrem Präsidentschaftsprogramm hat die Regierung bereits angekündigt, dass sie beim Follow-up zur Zukunftskonferenz einen „breiten Konsens unter den Mitgliedstaaten“ anstrebt – was auf ein langsames Vorgehen hindeutet, das viel Rücksicht auf die Bremser nimmt.

Doch Reformbedarfe verschwinden nicht, wenn man sie ignoriert, und so wird auch diese Debatte im neuen Jahr weitergehen. Voraussichtlich im Frühjahr will das Parlament einen detaillierten Vorschlag vorlegen, wie ein neuer EU-Vertrag aussehen könnte. Damit wird der Druck auf den Europäischen Rat steigen, sich dazu zu positionieren. Entscheiden die Staats- und Regierungschef:innen sich dann, einen Konvent zu eröffnen, so dürfte das eine Bündelung der Debatten erleichtern. Andernfalls werden der EU wohl weitere Monate oder Jahre zäher Verhandlungen über einzelne Reformdossiers bevorstehen.

Wahlrechtsreform: die nächste Blockade

Zu diesen Reformdossiers gehören auch die Überarbeitung des Europawahlrechts sowie des europäischen Parteienstatuts. Beide machten im vergangenen Jahr große Fortschritte und könnten im besten Fall 2023 zum Abschluss kommen. Im Falle der Wahlrechtsreform wäre das schon deshalb notwendig, weil nach den Empfehlungen des Europarats im letzten Jahr vor einer Wahl keine größeren Änderungen ihres Rechtsrahmens mehr durchgeführt werden sollen – und 2024 ja die nächste Europawahl ansteht.

Tatsächlich aber steht die Wahlrechtsreform derzeit kurz vor dem Scheitern, da mehrere Mitgliedstaaten die darin vorgesehenen gesamteuropäischen Wahllisten ablehnen. Dass das Parlament sich damit einfach abfindet, seinen in jahrelangem Ringen zwischen den Fraktionen erzielten Kompromiss fallen lässt und auf einen der wichtigsten Hebel für mehr europäische Demokratie verzichtet, ist allerdings kaum zu erwarten. Auch hier wird die Blockade im Rat also wohl nur dazu führen, dass sich eine überfällige Reformdebatte immer weiter hinzieht.

Kampf um den Rechtsstaat: Ungarn isoliert

Fortsetzen wird sich 2023 auch die Auseinandersetzung um die Rechtsstaatlichkeit in den Mitgliedstaaten. Seit Beginn des Kriegs in der Ukraine kam es zu einer Entzweiung zwischen der anti-russischen PiS/EKR-Regierung in Polen und der pro-russischen Fidesz-Regierung in Ungarn. Die Kommission versuchte sich das zunutze zu machen, um die Allianz zwischen den beiden Ländern auch in anderen Fragen aufzubrechen und die ungarische Regierung weiter zu isolieren.

Diese Strategie ging nur zum Teil auf: Im Rechtsstaatskonflikt stehen Polen und Ungarn grundsätzlich weiter Seite an Seite. Immerhin aber bewegte sich Polen zuletzt in einigen Punkten auf die Forderungen der EU zu. Was Ungarn betrifft, beschloss der Rat hingegen vor einigen Tagen, erstmals über den neuen Rechtsstaatsmechanismus Finanzmittel einzufrieren. Das neue Jahr wird zeigen, ob sich diese Maßnahme auch in der Praxis auf die Rechtsstaatslage in Ungarn auswirkt.

Parlamentswahlen in Polen, Spanien und anderen Ländern

Dass die polnische Regierung derzeit eher kein Interesse an einer Eskalation des Konflikts mit der EU hat, hat noch einen weiteren Grund: Im Herbst 2023 findet die nächste polnische Parlamentswahl statt – und den aktuellen Umfragen nach würde die PiS (EKR) dabei zwar erneut stärkste Partei werden, die von ihr geführte Regierung aber ihre Mehrheit verlieren. Es wird also ein spannender Wahlkampf, nach dem im besten Fall eine demokratische Koalition unter Führung der PO (EVP) die Rechtsregierung ablösen und den Rechtsstaat in Polen wiederherstellen könnte.

Polen ist allerdings nicht der einzige große Mitgliedstaat, in dem Ende 2023 gewählt wird: Auch in Spanien steht eine nationale Parlamentswahl an, bei der die aktuellen Umfragen einen sehr knappen Ausgang zwischen der regierenden Koalition aus PSOE (SPE) und UP (EL-nah) einerseits und einem möglichen Bündnis aus PP (EVP) und Vox (EKR) andererseits erwarten lassen. Gegebenenfalls könnte es hier (ähnlich wie 2019) zu einem Patt mit einer langen und schwierigen Regierungsbildung kommen. Für die EU wird das auch deshalb relevant, weil Spanien im zweiten Halbjahr 2023 die Ratspräsidentschaft innehat.

Weitere Parlamentswahlen stehen im Frühling in Estland, Finnland und Griechenland sowie im Herbst in Luxemburg an. Auch in Bulgarien könnte es eine vorgezogene Neuwahl geben – es wäre die fünfte in drei Jahren. Anfang Februar findet außerdem die Präsidentschaftswahl in Zypern statt, dem einzigen EU-Mitgliedstaat mit einem präsidialen Regierungssystem.

Bei den meisten dieser Wahlen haben die derzeitigen Regierungskoalitionen gute Chancen, ihre Mehrheit im Parlament zu halten. Knapp wird es in Finnland, wo Kokoomus (EVP) gute Aussichten hat, die SDP (SPE) als stärkste Partei abzulösen und die Regierungsführung zu übernehmen. Auch in Luxemburg und Bulgarien wird die derzeit oppositionelle EVP wohl wieder auf dem ersten Platz landen, dürfte sich danach bei der Suche nach Koalitionspartnern allerdings schwer tun. Läuft es gut für die EVP, könnte sie bis Ende 2023 also bis zu fünf zusätzliche Sitze im Europäischen Rat gewinnen. Auf Zypern tritt Amtsinhaber Nikos Anastasiadis (DISY/EVP) nicht mehr an; als Favorit für seine Nachfolge gilt Nikos Christodoulidis, der ebenfalls DISY-Mitglied ist, bei der Wahl jedoch als Unabhängiger kandidiert.

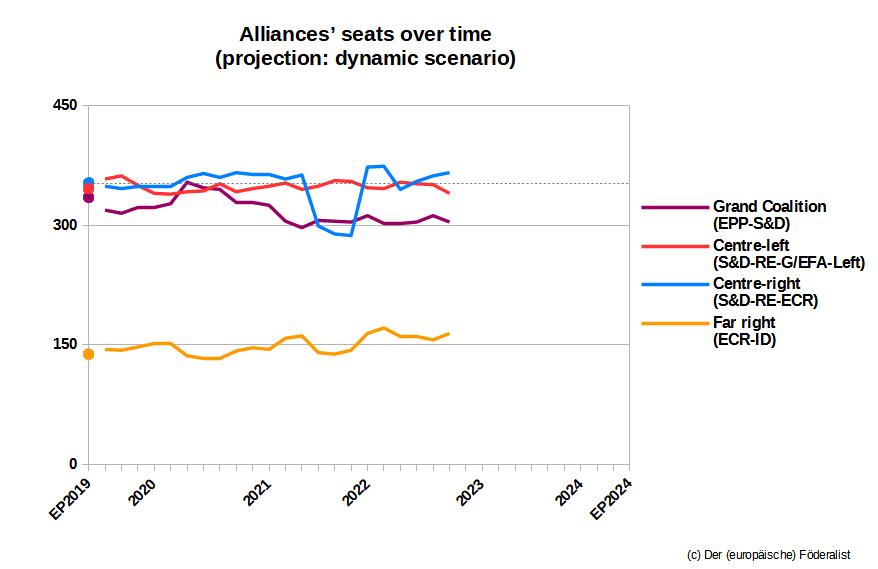

Europawahl 2024: das nächste Spitzenkandidatenverfahren

Aber nicht nur in den Mitgliedstaaten stehen Wahlen an – auch die EU selbst beginnt sich allmählich warmzulaufen für die Europawahl im Frühsommer 2024. Neben der schon erwähnten Wahlrechtsreform wird dabei vor allem die nächste Ausgabe des Spitzenkandidatenverfahrens im Vordergrund stehen. Dieses Verfahren, nach dem die europäischen Parteien bereits vor der Wahl Kandidat:innen für die Kommissionspräsidentschaft ernennen, ist bei den Staats- und Regierungschef:innen bis heute wenig beliebt.

Doch da die Parteien für die Nominierung von Kandidat:innen nicht auf die Zustimmung des Rates angewiesen sind, werden sie sich von den Vorbehalten der Mitgliedstaaten nicht abhalten lassen. Folgen sie dem Zeitplan vergangener Wahlen, werden sie bis Ende 2023, spätestens Anfang 2024 ihre Kandidat:innen ernennen. Im besten Fall werden wir im Laufe des Jahres also eine zunehmende transnational-parteipolitische Auseinandersetzung und Personalisierung europapolitischer Debatten erleben. Im schlechteren droht hingegen eine Neuauflage der ewigen Debatte darüber, ob die Spitzenkandidat:innen am Ende für die Wahl der nächsten Kommissionspräsident:in überhaupt relevant sein werden.

Eppur si muove?

Blockade oder Bewegung – das wird für die EU die große Frage im Jahr 2023 sein. Im Jahr 1 nach der Zukunftskonferenz und der viel beschworenen „Zeitenwende“ zeigt sich ein institutioneller Reformstau, in dem die Mitgliedstaaten in vielen Bereichen Fortschritte verhindern, die dringend notwendig wären, um die EU zugleich demokratischer und handlungsfähiger zu machen.

Vieles spricht dafür, dass dies auch in den nächsten Monaten so bleiben wird. Gelingt es den Regierungen jedoch, hier über ihren Schatten zu springen, so könnte das neue Jahr der Anfang einer Relance werden, die Vertiefung und Erweiterung des europäischen Projekts zugleich in Angriff nimmt.

Auch für den Betreiber dieses Blogs geht das neue Jahr mit Veränderungen einher: Nach einem Jahr an der Universität Duisburg-Essen werde ich im Januar 2023 als Senior Researcher an das Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA) in Helsinki wechseln. Wie bisher werde ich mich auch dort mit Fragen der EU-Reform und der supranationalen Demokratie beschäftigen, und natürlich wird auch dieses Blog weiterhin die europapolitische Debatte begleiten. Erst einmal aber geht „Der (europäische) Föderalist“ in seine alljährliche Winterpause. Allen Leser:innen frohe Feiertage und ein glückliches und gesundes neues Jahr! |