In early June 2005, the then Luxembourg Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker gave a speech at the German military cemetery Sandweiler in Luxembourg. A few days earlier, a majority of referendum voters in France and the Netherlands had rejected the ratification of the EU Constitutional Treaty; one of the biggest steps towards deepening the European Union in decades was about to fail. In this situation, Juncker reminded his public of what, in his view, constituted the real meaning of European unification:

“Those who doubt Europe, those who despair of Europe, should visit military cemeteries. Here you can see what non-Europe, the antagonism between the peoples, must lead to. Military cemeteries are therefore lasting testimonies to the sacred duty of not letting European friendship end.”

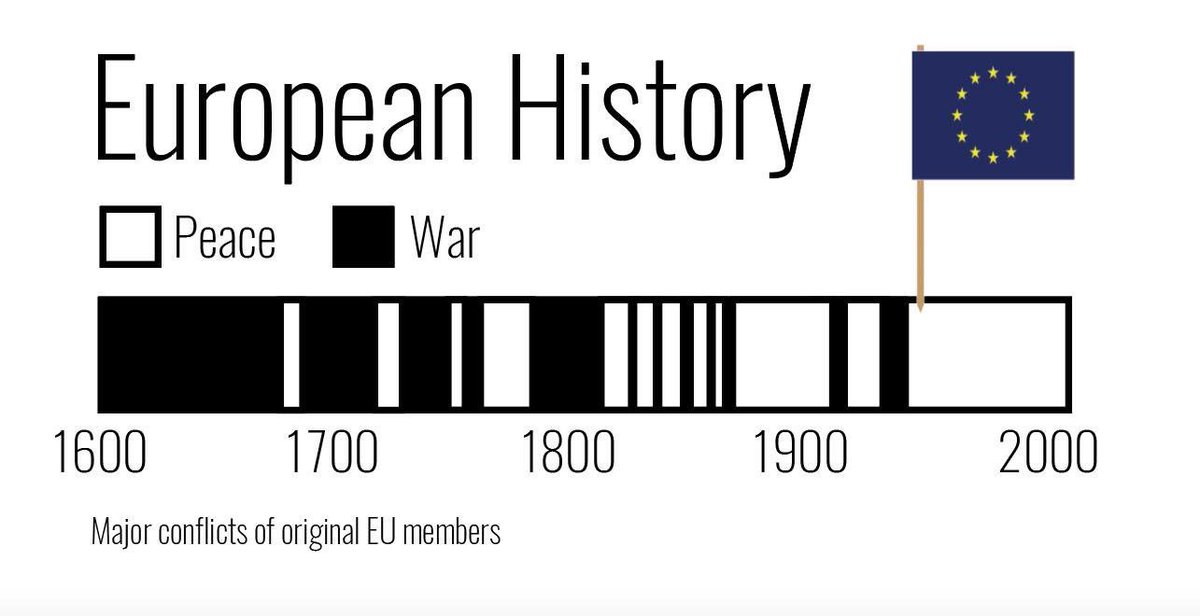

Juncker’s argument recalled one of the oldest and most widespread narratives of European integration: the idea that the EU serves to avoid armed conflicts between its member states. This narrative is deeply anchored in the minds of Europeans: in the Eurobarometer surveys, peace is regularly ranked among the top achievements of the EU. But the origin of the idea of ending wars among European states through supranational institutions is much older than today’s EU. This blog post outlines how it has changed over time, developing from a utopian vision to a revolutionary project, and finally to a conservative, status-quo preserving argument.

Early proposals of peace through integration

In fact, the concept of sovereign nation states had only just taken root in early modern Europe when political thinkers already began to criticize it as incapable of guaranteeing peace. Most of these critics saw the main reason of war in the lack of an effective law that could contain and resolve power struggles between sovereigns. In order to create lasting peace, it was therefore necessary to have common rules respected by all states. To adopt and enforce these rules, supranational institutions were needed.

However, early proposals differed widely on how exactly these institutions should be designed. For example, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his 1795 essay On Perpetual Peace, developed the vision of a supranational “federation of free [democratic] states” that would guarantee each other’s freedoms and thus live together in peace. However, Kant conceived this “federation of free states” as a purely legal order designed to avoid political interference.

On the other hand, the American politician William Penn had developed a much more agency-centred model a century earlier. In his 1693 Essay on the Present and Future Peace of Europe, he proposed a kind of permanent conference of European princes whose delegates would jointly deliberate on cases of conflict and take joint action against rule-breakers. Unlike Kant, Penn proposed few substantial rules, but placed far greater emphasis on the conference’s deliberative and voting procedures. As a consequence, his proposal much more resembled an additional level of government with its own agency and scope for supranational decision-making.

In the 19th century, the international peace movement took up the idea that war could only be avoided through a supranational order that restricted national sovereignty. Its activists mainly focused on the codification of international law and supranational arbitration mechanisms, leading to the establishment of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 1899. Sometimes, however, this approach was also linked to the idea of a supranational government or parliament. The opening speech of the 1849 World Peace Congress in Paris, in which the French writer Victor Hugo outlined his vision of a “United States of Europe”, is a prominent example.

From utopia to political project

For a long time, however, these plans had no real chance of becoming reality. For most political rulers, war was still too commonplace and (almost) unrestricted national sovereignty too important to consider permanently foregoing them. This changed with the horrors of World War I: In 1919, the League of Nations was founded as the first real attempt at an international peace organisation. However, due to the unanimity principle and the lack of enforcement instruments, it quickly proved ineffective on important issues. Aggressive nationalism remained widespread and caused growing concerns about new military conflicts.

As a consequence, the need to go beyond the League of Nations in order to secure lasting peace became a leitmotif for the emerging pro-European associations. Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, the founder of the Pan-European Union, took up the idea of obligatory supranational arbitration in his Pan-European Manifesto of 1923. The emerging federalist movement, by contrast, criticised this approach as insufficient. The British federalist Philip Kerr (Lord Lothian) argued in his 1935 lecture Pacifism Is Not Enough that states would not necessarily obey a court of arbitration, so that its rulings might have to be enforced militarily – which would again leave the question of war and peace to the individual states. Therefore, a supranational democratic federal state was the only solution that could ensure the acceptance of a common legal order without resorting to the use of force.

This idea also influenced the Italian anti-fascist Altiero Spinelli, who developed Lord Lothian’s logic into a radical political programme. In the 1941 Ventotene Manifesto, he claimed that after World War II, a “revolutionary movement” would have to overcome the division of Europe into sovereign states so that they would not “turn peoples into armies” again.

A solution to the German problem

Not everyone shared Spinelli’s radicalism, and the revolution he had in mind failed to materialise. Nevertheless, after the war the idea that a united (Western) Europe was needed to maintain peace was more popular than ever. The main focus was now on the “hereditary enemies” Germany and France, whose reconciliation was to form the basis for the economic reconstruction of the continent.

In his famous 1946 Zurich speech, the British wartime prime minister Winston Churchill spoke out in favour of “a kind of United States of Europe”, but only referred to the models of the Pan-European Union and the League of Nations, ignoring more far-reaching federalist demands. Similarly, the 1948 Hague Congress of the European Movement declared that “the integration of Germany in a United or Federated Europe alone provides a solution to […] the German problem”, but its specific institutional proposals were limited to a parliamentary assembly, a human rights charter and a human rights court – proposals that were later implemented through the Council of Europe.

“De facto solidarity”: peace through interdependence

In the meantime, a new line of thinking about peace and integration emerged during and shortly after World War II. Unlike most earlier approaches, it focused less on political than on economic and societal causes of war, and saw the solution to them less in supranational legal institutions than in transnational social interdependence.

The main advocate of this approach was the Romanian-British political scientist David Mitrany. In his 1943 paper A Working Peace System, Mitrany criticised the federalist demands as unrealistic. Instead, he proposed a system with a multitude of individual supranational agencies that would solve specific cross-border problems. In this way, over time, “the interests and life of all the nations would be gradually integrated”, national antagonisms would become less important and an “international society” would emerge.

After the war, this “functionalist” approach to peaceful integration became a crucial inspiration for the creation of today’s European Union. The idea of issue-specific agencies was a cornerstone of French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman’s proposal to establish a European High Authority for Coal and Steel, which later developed into today’s European Commission. The central argument in Schuman’s famous declaration of 9 May 1950 was, once again, the prevention of a new war between Germany and France. Under the premise that “world peace cannot be maintained without creative efforts proportionate to the dangers which threaten it”, he argued for a common European framework for the coal and steel production. By this, new cross-border production chains should replace the national cartels that had so far dominated in this key area of the defence industry – a “de facto solidarity” which, according to Schuman, would make a new war “not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible”.

From political project to everyday reality

During the following years, functionalist and federalist approaches competed and complemented each other in the shaping of the European institutions. After the success of the Schuman Plan, the economic and social entanglement between member states continued with the single market and the growing intra-European migration. At the same time, the EU also developed a strong supranational constitutional order with a dense legal system, an independent Court of Justice, regular Council meetings, and even a directly elected European Parliament. Finally, all member states are democracies – at least in theory, given the recent democratic backsliding in several countries.

Thus, whether the main conditions for lasting peace are seen in the way of Kant (a common legal order among democratic states), Penn (a supranational legislative, judiciary and executive power) or Mitrany (transnational social interdependence managed by supranational agencies), the EU satisfies all these criteria. And indeed, its peacekeeping achievements are remarkable. For many member states, the last military conflict with a neighbouring country was three or more generations ago. Today, the permanent absence of war in Europe is no longer a utopian vision, but – at least among EU members – an everyday reality.

Losing salience

This success also had consequences for the peace narrative itself. As early as the 1950s, new military conflicts between Western European countries were no longer viewed as an acute danger. On the contrary: In the emerging Cold War, the EC members were partner states within the Western alliance. As a consequence, peace quickly lost its central importance to the debate on Western European unification. At ceremonial occasions, politicians would continue to remind of Europe’s peacebuilding effect, but they hardly derived any specific demands for action from this argument.

Only in very isolated cases, there were exceptions to this. The peace narrative became prominent once again for a short time in late 1989, when the fall of the Berlin Wall shook up the political equilibrium in Europe and raised concerns of a German “Fourth Reich” that could become a threat to its neighbours. To counteract these fears, the German and French governments promoted a “European embedding” of German reunification. With the monetary union created in the Maastricht Treaty, the member states consciously made themselves dependent on each other – a new example of “de facto solidarity” capable of restoring trust between governments. However, in the debate on monetary union these peace considerations always coexisted with economic arguments and lost salience again after 1990.

Apart from that, the peace argument was particularly important in the debate on the accession of new member states. The 2004 Eastern enlargement, when eight former communist countries joined the EU, was celebrated as a “European reunification” that sealed the end of the Cold War on the continent. At the same time, the prospect of joint EU membership helped defuse resurgent border and nationality conflicts in Central and Eastern Europe – for example between Hungary and Slovakia. Today, the EU membership perspective for the Western Balkan countries is intended to provide an incentive for peace after the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. In this context, a concrete need for political action can still be derived from the peace argument: to continue to keep the doors of the EU open for new accession candidates who meet the necessary requirements.

A narrative for the preservation of the status quo

During the European “polycrisis” of the last decade, finally, the peace narrative has increasingly taken on a new function. In the face of numerous integration setbacks, pro-Europeans have started to use it as a standard argument to defend the European Union and to warn of its possible collapse.

Jean-Claude Juncker’s military cemetery speech responding to the failure of the EU Constitutional Treaty in 2005 is just one example for this. Another one is the Nobel Peace Prize, awarded to the EU at the height of the euro crisis in 2012. The stated reasons by the Nobel Committee clearly implied that this award was meant to support European integration against growing criticism and fears of disintegration. The EU, it said, was “currently undergoing grave economic difficulties and considerable social unrest”, but the “most important result” of European unification remained its “successful struggle for peace and reconciliation”.

Four years later, UK Prime Minister David Cameron tried without success to use the peace narrative for the Remain campaign ahead of the 2016 Brexit referendum. A few weeks before the vote, he warned that leaving the EU could increase the risk of war in Europe and, much like Jean-Claude Juncker before him, recalled the “rows of white headstones in lovingly-tended war cemeteries”. In the same year, the Europe-wide electoral successes of right-wing populist parties prompted the citizens’ movement Pulse of Europe to issue a similar warning: “The European Union was and is first and foremost an alliance to safeguard peace. This peace is now threatened both internally and externally through nationalist and protectionist tendencies. If one wants to live in peace, one must strengthen European unity and not allow Europe to become divided!”

Increasing rigidity

The peace narrative, which in the Schuman Declaration was still associated with the demand for “creative efforts”, has thus become a defensive and conservative argument. Instead of shaping the future and advancing European integration in a certain direction, it aims at preserving what the EU has achieved in the past and protecting its status quo.

This defensive and sometimes apologetic use of the peace narrative is giving it an increasingly rigid and almost ritualistic character. At the same time, it does not seem to provide any answers to the most pressing questions with which the European Union is confronted today. How can transnational interdependence be reconciled with democratic self-government? How can the economic gains, but also the burdens of the single market and the monetary union be fairly distributed? How can the rule of law and media freedom in the EU be protected against increasingly authoritarian national governments? In any meaningful discussion about the current challenges of European integration, the absence of internal war is no longer the goal, but at best the starting point.

From everyday reality to obsolescence?

In the future, this sense of obsolescence of the peace narrative could increase even further with the emergence of a more and more transnational European society. The logic of the narrative is implicitly based on the division of Europeans into national peoples, but this division is prone to become less important as both the realities of life and the political self-images of European citizens are less tied to nation states. On the one hand, migration experiences and transnational family histories are leading to new, hybrid identities, for which the growing (albeit still minoritarian) number of dual citizens is only a symbolic indicator. On the other hand, the gradual parliamentarization of the EU’s political system is increasing the importance of pan-European political parties, which offer a projection surface for supranational political identifications that transcend national perspectives.

Even if so far only few European citizens really perceive EU politics from such a supranational perspective, these trends could be an indication of the peace narrative’s future. In a sense, they are the logical continuation of the traditional European peace agenda, a culmination of both the functionalist approach of fostering a transnational society and the federalist approach of creating supranational democratic institutions. At the same time, however, they also make the peace narrative itself appear more and more anachronistic – striving for “good neighbourliness” or “friendship” among European nations no longer makes sense if the cultural and political traditions of these nations flow together in the self-image of individual citizens. The emergence of a transnational society with supranational political identities might therefore be the vanishing point of the European project of peace through integration.

This article first appeared on the blog “Stories of Europe”, edited by the Centre of Excellence in Law, Identity and the European Narratives (EuroStorie) of the University of Helsinki. From January to July 2021, the author has been a visiting researcher at EuroStorie, supported by a Re:constitution fellowship.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen

Kommentare sind hier herzlich willkommen und werden nach der Sichtung freigeschaltet. Auch wenn anonyme Kommentare technisch möglich sind, ist es für eine offene Diskussion hilfreich, wenn Sie Ihre Beiträge mit Ihrem Namen kennzeichnen. Um einen interessanten Gedankenaustausch zu ermöglichen, sollten sich Kommentare außerdem unmittelbar auf den Artikel beziehen und möglichst auf dessen Argumentation eingehen. Bitte haben Sie Verständnis, dass Meinungsäußerungen ohne einen klaren inhaltlichen Bezug zum Artikel hier in der Regel nicht veröffentlicht werden.