- Minna Ålander, German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), Berlin

- Carmen Descamps, German Embassy, Madrid

- Manuel Müller, University of Duisburg-Essen / Der (europäische) Föderalist, Berlin

- Julian Plottka, University of Passau / University of Bonn

- Sophie Pornschlegel, European Policy Centre, Brussels

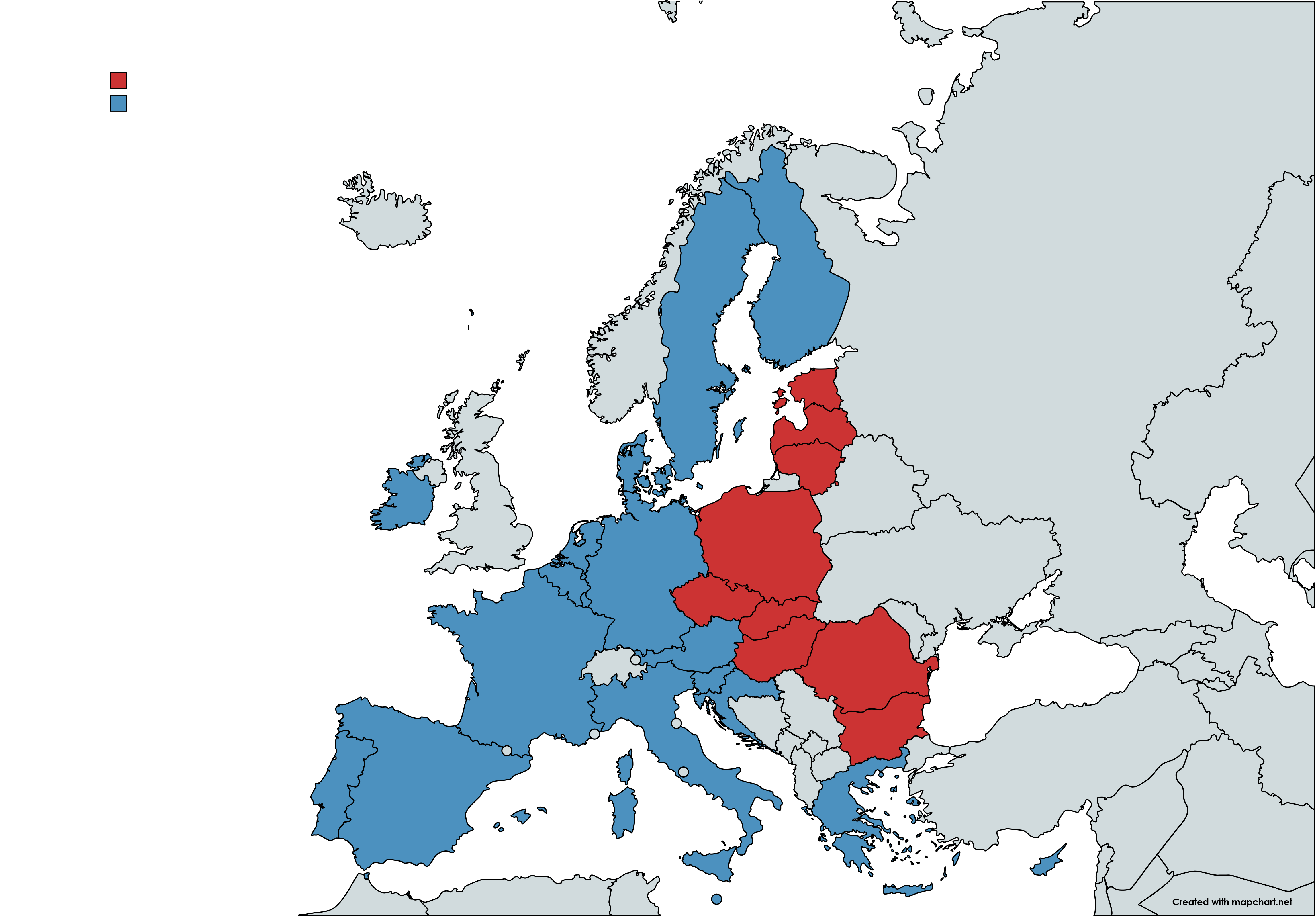

- EU Member States in Northern Europe (orange) and in Central and Eastern Europe (red), according to EuroVoc classification.

Manuel

The Russian attack on Ukraine has also changed the EU in recent months. Among other things, the informal country groups and alliances between governments in the Council have shifted: northern and eastern member states that are calling for a tough stance on Russia have moved closer together. Poland and Hungary, who had long been close allies in the Visegrád Group, have split over the war. But also Germany and France are coming in for sharp criticism from the Northern, Central and Eastern European states.

Today’s European Policy Quartet is, in fact, a quintet: we are joined by Minna Ålander from the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. Minna, a few weeks ago you coined the acronym NCEE (“Northern, Central and Eastern Europe”) on Twitter, which has since spread. Would you like to start by telling us who exactly you mean by NCEE – and what common interests and positions are uniting these countries?

What unites NCEE?

Minna

I have observed during the spring that the Northern, Central and Eastern European countries are increasingly taking a unified position towards Russia in the war against Ukraine. NCEE is not a fixed or formalised group. For me, it includes the Nordic and Baltic countries, the Central-Eastern European countries except Hungary, but also South-Eastern European countries like Romania. In other words, the countries in Russia’s (direct) neighbourhood or that Russia potentially sees in its sphere of influence. Recently, however, it was particularly the Nordic states that have become more visible within the group.

The lowest common denominator of the NCEE has emerged to be criticism of, or opposition to, the Franco-German position – which in the meantime has gotten a little out of hand in some cases. The frustration with Scholz and Macron, especially because of their ambiguous communication, has grown to such an extent that they are now seen as capable of anything, the dirtier the better. As a consequence, the differences between justified criticism and “bashing” are becoming increasingly blurred.

Carmen

… which is also interesting insofar as this (unified) Franco-German position doesn’t necessarily always exist. But more on that later, I’m sure.

The Brexit orphans

Julian

I think “lowest common denominator” is a good keyword here. When we talk about groups of countries in the EU, the discussion is always based on the assumption that the respective group has common interests in different policy areas. With regard to the NCEE, I don’t see that. Except for the policy towards Russia, the positions seem to me to be too different in many fields – and even on Russia there are individual governments with divergent attitudes. I therefore don’t think that the NCEE countries as a group will become a formative force in Europe.

Minna

What the NCEE countries had in common before was that they were strongly oriented towards the United Kingdom. The Nordic member states have really hidden behind the UK, relying on it to block everything they don’t want either, without having to articulate it that way themselves. Since Brexit, they increasingly find that a counterweight to the “Franco-German engine” is missing.

Julian

You are certainly right about that. And the NCEE countries are not alone in this – I would even say that it is often a problem for Germany too that the UK now no longer says “no” as a proxy state.

However, no policy can be made out of a rejection of further integration. They may be united in refusal, but they won’t achieve much that way. Instead of asserting their interests, they will just get caught in a Eurosceptic trap. After all, that was the real tragedy of British European policy, too.

Joint rejection of treaty reforms

Manuel

Yes, this pattern is also visible with regard to the follow-up to the Conference on the Future of Europe: the “Non-Paper of the 13”, in which a group of governments rejected treaty reforms on 9 May, was signed almost exclusively by Northern, Central and Eastern European countries. So here the NCEE countries have a common position on an issue that has nothing to do with Russia, but it is essentially a blocking position.

Minna

Still, the opposition to treaty reform in the NCEE countries is probably less about rejecting treaty change per se. It is about a (partly irrational) fear that Germany and France would use the opportunity to develop the EU in a (federal) direction that is not wanted in NCEE. Instead, the NCEE countries support a quick admission of Ukraine – so what is at stake is basically the old opposition of “deepening vs. widening”.

- Signatory states of the „Non-Paper of the 13“.

This has a variety of reasons: the Central and Eastern European countries have only recently regained their independence and therefore place a lot of value on national sovereignty. The Nordic EU members, on the other hand, are often only half-in anyway and don’t see EU integration as a primary national goal. For example, Denmark joined in the 1970s, but has many opt-outs; Sweden is not in the Eurozone; and Finland joined in the 1990s mainly for security reasons, although the EU is not primarily a security union.

All in all, thus, there is little appetite for further transfers of competences. And stoking this fear of Germany and France is a common Eurosceptic strategy, at least in Finland.

Anti-federalism without alternative proposals?

Manuel

For me, this “small-country antifederalism” is an interesting phenomenon. I understand the idea of insisting on veto rights as a protection of national identity. But in the end, having more veto rights and fewer competences for supranational institutions means most of all that more decisions are taken intergovernmentally. And more intergovernmentalism means that the large member states can better play to their strengths.

Historically, among the founding members of the EU, it was “large” France that was intergovernmentalist, while the “small” member states (then the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) advocated a strong Commission and European Parliament. The fact that federalism is now seen as a demand of the “large” countries, against which the “small” NCEE countries believe they have to defend themselves, is a strange reversal.

Julian

The other side of the coin, of course, is that states like Denmark, with its previous opt-out from Common Security and Defence Policy, or Poland, outside the Eurozone, are panic-stricken that policy will be shaped without them …

Sophie

And this despite the fact that small states are even overrepresented in the EU. If they don’t like the policies of France and Germany, they should make alternative proposals for further integration. I don’t see any so far.

That the NCEE countries expressed their opposition to treaty reforms in the non-paper of 9 May, but at the same time are in favour of EU enlargement, also seems somewhat contradictory to me. Unless they intend to make the EU even more incapable of action.

Julian

Yes, exactly. Since they can’t agree on anything positive and constructive, they don’t participate in shaping policy.

Minna

In any case, I also observe a kind of “renaissance” of European identity in the North (and I think at least partly in the East as well). We have now seen how Ukraine is literally fighting with its life for the EU perspective. This has somehow enhanced the EU.

Where do the Netherlands stand?

Carmen

Hello everyone – I was offline for a moment. But now my internet is back up! 😊

Short question: Where do we place the Netherlands in this coordinate system today? I don’t want to take the blame game too far, but if we are talking about proxy states with concerns about deeper integration, especially in the post-Brexit perspective, that is something we should at least mention.

Minna

The Netherlands have traditionally been a core member of the Frugal Four. But there are signs that their position may be changing.

Sophie

I think Brexit has led to the Netherlands having to reorganise its European policy. Which is not a bad thing – the joint paper with Spain on economic reform surprised me positively. And in the area of the rule of law, the Netherlands has recently positioned itself more strongly, too.

Manuel

Yes, interesting point! After the failed referendum on the EU Constitution in 2005, many Dutch parties first developed a great distrust of further supranationalisation. It will be interesting to see whether there is now a swing back to more integration-friendly positions.

Carmen

I share your impression regarding the Frugal Four and the repositioning after Brexit – I had noticed similar things myself and wanted to check whether you also see it that way. The Spanish-Dutch financial paper in particular was interesting because it went across an old line of confrontation. Let’s wait and see what’s still to come.

Reproaches to Emmanuel Macron

Sophie

I think we should come back to the role of France and Germany. Both countries are currently under heavy criticism because of the war in Ukraine, but actually their positions are very different. On the one hand, Germany is in an identity crisis (are we still pacifists if we supply heavy weapons to Ukraine?). In France, on the other hand, Macron was in campaign mode for the presidential elections. He used the war in Ukraine above all to show that a capable and experienced president is needed.

So the domestic political realities in both countries are very different – and the attitude towards Russia doesn’t seem to me to be the same in France and Germany either.

- EU member states in which a proportion of the population above the EU average (24%) fears the Ukraine war could spread to their own country (Eurobarometer, June 2022).

Minna

That’s right. But the perception in NCEE is that both Germany and France tend to think that we will have to rebuild relations with Russia at some point and therefore should not burn all bridges now. Among the NCEE countries, on the other hand, the prevailing view is that the most important thing is to make sure that Russia can’t attack any more neighbours – so they would be happy to finish Russia off.

Sophie

After his speech on 9 May, Macron was sometimes accused of being indulgent with Russia because he said that dialogue with Putin should be maintained. Unfortunately, it seems to me that a lot of nuance was lost in the reporting. After all, Macron also strongly criticised Russia in the speech.

To me, Macron just seems to be taking a very realpolitik perspective: We will not get rid of Putin so easily in the near future and therefore have to look for a solution with him. Of course, this is also controversial, because other countries tend to take the position that we should in no way speak of an end to the war now.

Minna

Exactly. The controversy is mainly about when and under which conditions the war should end. And in the NCEE countries there is concern that France and Germany are prepared to sacrifice the security interests of Russia’s neighbouring countries for a quick end to the war.

Carmen

I would go back a step from the end of the war and also think about the sanctions against Russia. Both Germany and France are urged to push for quicker and more far-reaching sanctions. But for all their similarities, the countries still have national differences and interests. For example, in the energy sector: Germany’s dependence on Russian gas is currently 35% (in 2021 it was still 55%); France’s is 20%. For other countries, these numbers may be significantly lower; my current host country Spain, for example, only imports 9% of its gas from Russia.

With this example, I want to show that Germany and France are confronted with different challenges. Therefore, “not burning all bridges with Russia” does not mean not taking action or not showing willingness to help a neighbour state of the EU that Russia has invaded in violation of international law. Rather, it means proceeding in a well-considered, well-dosed and efficient manner. The external perception of the “Franco-German tandem” does not necessarily coincide with the internal perception here.

Remembering the euro crisis

Manuel

In this context, an interesting point for me are the parallels between the anger of the NCEE countries now and the anger of the Southern European countries during the euro crisis ten years ago. Both cases are about transnational solidarity – in terms of financial policy then, in terms of security policy today. And in both cases, Germany does not cut a good figure, although from its own point of view it is quite willing to go along with common measures and only wants to protect some of its own legitimate national interests.

Minna

Indeed – and many bad memories from the euro crisis have now come up again in the South. When it was argued in Germany at the beginning of the war that Germany could not reduce its energy dependence on Russia more quickly because of the economic consequences, this caused some sharp comments in the countries that at the time were pushed into massive austerity. But the Berlin policy bubble is remarkably resistant to feedback from outside …

Sophie

Yes! Germany is also heavily criticised in Brussels. Of course I can understand that the political issues that the Ukraine war has raised in Germany need to be discussed. But right now, it seems to me that Berlin’s politicians are only preoccupied with themselves and have no understanding whatsoever of Germany’s actual position in Europe.

Criticism of Germany from abroad is either rejected or ignored. But if you see yourself as pro-European, you should focus on dialogue instead of simply waving your neighbours away when they say something you don’t like.

I was also intrigued by Scholz’s statement that he didn’t want to go it alone when it came to arms deliveries. In my view, he used the need to consult with European partners as a pretext here to divert attention from the internal party and government conflicts that are the real problem and lead to Germany’s hesitancy.

Minna

The good old German manoeuvre of hiding behind a European justification so you don’t have to speak openly about your own interests …

The dilemma of the large countries

Sophie

That is the dilemma of the large countries in European politics: the bigger you are, the more criticism you naturally receive from other EU member states.

Nevertheless, I would say that large countries have to put up with that – what matters is that you move forward somehow instead of doing nothing at all. As a colleague of mine once called it: better “muddling through upwards” than “muddling through downwards”.

Minna

Yes, Germany has ignored the security responsibility that comes with economic leadership for too long.

Carmen

I don’t want to take a position on this, but I think the following is striking, too: If a member state like Germany lacks European coordination in a political decision, especially in conflictive ones, it is quickly accused of going alone. The refugee policy during the summer of 2015 is just one example. If, on the other hand, the public thinks that a member state acts too slowly or too cautiously, it is said to hide behind European policy positions. Isn’t that a bit like “damned if you do, damned if you don’t”?

Sophie

In the end, the basic problem is that there is little leadership in European politics right now. Apart from Macron, there are few who really have a strategic vision for the EU. The traffic light coalition may have been ambitious in its coalition agreement, but since then nothing has come out of Germany. And of the EU institutions, only the European Parliament seems ambitious to me. The Commission is looking to the Council, and the Council is mainly following its tradition – to water down and delay, no matter what.

What distinguishes NCEE from the euro crisis countries

- Member states of the Bucharest 9 Format.

Julian

Coming back to Manuel’s parallel to the crisis in the euro area: the two debates aren’t completely comparable, after all. At the time, the German position didn’t only follow German interests, but also an economic policy view that had been mainstream for a long time since the 1980s. In the course of the crisis, the economic policy mainstream then shifted towards more left-leaning positions, and it took a while for Germany to follow suit. So I would say that Germany simply pursued an old policy for too long (after it had also started to apply it later than the rest of the world).

In defence policy, by contrast, I think there has never been such a dominant mainstream. Europe has always been characterised by a variety of different strategic cultures that have led to strong controversies about security policy. And they still do today: In Austria, support for neutrality remains high in the current situation – quite unlike Finland and Sweden. The simplest solution to this dilemma is a further supranationalisation of the EU.

Manuel

Yes, that may be. In my view, another difference between the euro crisis and today is that, at the time, the governments of the crisis countries, especially Italy and Spain, quite cleverly sought to ally themselves with the EU institutions and propose “European” solutions to their problems. And in the end, a solidarity-based, European fiscal policy approach indeed prevailed in the Corona crisis.

This is hardly the case with the NCEE countries so far – we’ve talked about anti-federalism before –, even though the European Parliament and the Commission are actually very much on the same page with them regarding Ukraine.

Minna

Yes – I’m curious whether NCEE will now start to shape European policy more proactively. And what comes out of it … probably not quite what Germany and France are hoping for.

The feeling of being on the right side

Julian

That the NCEE governments don’t ally themselves more strongly with the supranational institutions is quite logical insofar as a call for European solutions would contradict their emphasis on national sovereignty. The Southern states are simply more pro-European and see the potential of European policy, which the NCEE countries are ready to forego on principle.

Minna

For NCEE, there is also the dilemma that anti-Franco-German sentiment is being exploited for the Brexit narrative – that is, that the UK is the only true partner of the NCEE countries and that Germany and France cannot be relied upon. For many in the NCEE countries, the anger at Germany and France is currently so great that it blinds them somewhat.

Manuel

Another difference, perhaps: During the euro crisis, there was no common identity among the affected states. They were angry with Germany, but not proud of being a crisis country. The derogatory acronym “PIIGS” had been ascribed to the group from outside and was rejected in the countries themselves. Moreover, governments were of course afraid that a common “crisis country identity” could facilitate that the aggravation of economic problems in one country would spill over to others.

In comparison, the NCEE countries are much more self-confident on the Russia issue. They see themselves as the ones who recognised the danger of Putinism early on, while Germany and France have not taken a clear stance until today. This feeling of being on the “right” side could explain why the Nordic and Baltic countries in particular are increasingly developing a transnational identity, but are less willing to embrace supranationalism than the crisis countries ten years ago.

Sophie

This is the whole problem of the current discussions: a moral debate is being superimposed on foreign and security policy issues.

A new leadership role for Poland?

- Minilateral alliances: Nordic-Baltic 6 (red) and Visegrád 4 (orange).

Manuel

Another important point for me is the new role of Poland in this constellation. Traditionally, the Franco-German engine of the EU has functioned mostly because Germany and France could negotiate bilateral compromises on behalf of the EU as a whole. In this constellation, France typically represented the interests of the southern and western states, Germany those of the northern and eastern states.

But if the Northeast no longer feels represented by Germany and Germany and France come under joint criticism, this model will no longer work. And since the United Kingdom is no longer available as a proxy either, Poland – as the largest of the Central and Eastern European member states, traditional advocate of a hard anti-Russia line and sceptic of supranationalism – could now become the “champion” of the NCEE countries. Given the rule of law situation in Poland, this would of course be problematic, to say the least.

Minna

I don’t think Poland has a chance there. The Nordic countries in particular clearly belong to the hawkish camp on questions of the rule of law. The core of the NCEE is rather a new cohesion among the Nordic and Baltic countries, based above all on common security interests in the Baltic Sea region.

Manuel

But is this rejection of Polish leadership among the Nordic-Baltic countries really so stable? To take just one example: When the former Estonian president Toomas Hendrik Ilves recently criticised the fact that the three “Western” heads of state and government Scholz, Macron and Draghi wanted to travel to Ukraine together, he brought Polish president Duda into the picture on his own initiative. (In the end, it was Romanian head of state Klaus Iohannis who was in Kyiv with the three).

Minna

Well, CEE has existed as a group of states for a long time – the N, i.e. the Nordic countries, have been added now. Ilves argues that the CEE countries, including the Baltic states, have often been ignored in the EU and that decisions have been taken over their heads. Some in the Baltic states therefore find it almost a little funny that the Nordic countries are now also experiencing this Baltic treatment, with which they themselves have been struggling for some time – so it’s a bit like they are saying “Welcome to the club”.

But that’s a view that is not necessarily shared in the Nordic countries. I don’t see a willingness there to be represented by Poland.

The Commission and the rule of law in Poland

Sophie

That’s good! I’m very critical of the EU Commission’s current positioning on the rule of law in Poland. By approving Poland’s Corona recovery plan, the EU has given away a trump card without requiring Poland to implement sufficient reforms in the justice sector. This is dangerous: You cannot oppose Putin’s autocracy and at the same time allow the same repressive methods within the EU.

What the Commission is hoping for is that Poland and Hungary will no longer “cover” each other in the Article 7 procedure because of their different positions on Russia. The EU’s more lenient attitude towards Poland and a tougher stance towards Hungary are supposed to create a rift between the two countries. But this does not change the fact that the Polish PiS government is dismantling freedoms in its own country.

Julian

The mechanism you describe is, of course, the real potential of “minilateralism”. This concept means that groups of states take joint positions – which always involves the danger of bloc formation, but also has the advantage that it reduces the complexity of decisions. If member states of such groups use their partial congruence of interests in order to pre-formulate package solutions to issues on which there is internal dissensus, then minilateralism increases decision-making efficiency in the EU and helps to overcome blockades.

However, this requires that the opportunity to find package solutions is actually seized and that bargaining chips aren’t abandoned for the sake of geopolitics.

Sophie

Yes, but that is exactly the problem: The Commission treats fundamental values like any other policy aspect that can be negotiated. But when human rights and the rule of law in one’s own country become the subject of negotiation, this is highly problematic. It is already in the word “fundamental values”: These are the basic preconditions before one even starts to negotiate!

Will the divide remain?

Manuel

Last question: Will the Southwest-Northeast divide become a permanent issue in the EU or not?

Carmen

No, I think – and hope – it won’t.

Julian

No, the two groups of countries are far too heterogeneous for that.

Carmen

Exactly, the states are too different from each other and the positions differ too much depending on the policy field – finance, security, rule of law, integration depth. What will remain, however, is that the alliances within the EU are dynamic and a European consensus will be increasingly difficult to achieve with 27 member states (or more?!).

Minna

The conflict between widening and deepening will certainly remain. Apart from that, the divide will remain an issue at least as long as the war lasts. Unless Macron and Scholz were to suddenly supply Ukraine with lots and lots of weapons … 😉

Sophie

The future of this division will strongly depend on how the war in Ukraine develops. I hope that it does not permanently lead to greater fragmentation in the EU.

However, I also wouldn’t advocate for an absolute unity of all 27 member states at any price. I would just like to see some groups of countries try to move the EU forward in some policy areas – because this is urgently needed.

Minna Ålander is a research assistant at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) in Berlin. |

Carmen Descamps is Deputy Head of Unit for Economy at the German Embassy in Madrid. |

|

Julian Plottka is a research associate at the Jean Monnet Chair of European Politics at the University of Passau and at the University of Bonn.

|

|

Sophie Pornschlegel is a Senior Policy Analyst at the European Policy Centre in Brussels.

|

The contributions reflect solely the personal opinion of the respective authors.

Previous issues of the European Policy Quartet can be found here.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen

Kommentare sind hier herzlich willkommen und werden nach der Sichtung freigeschaltet. Auch wenn anonyme Kommentare technisch möglich sind, ist es für eine offene Diskussion hilfreich, wenn Sie Ihre Beiträge mit Ihrem Namen kennzeichnen. Um einen interessanten Gedankenaustausch zu ermöglichen, sollten sich Kommentare außerdem unmittelbar auf den Artikel beziehen und möglichst auf dessen Argumentation eingehen. Bitte haben Sie Verständnis, dass Meinungsäußerungen ohne einen klaren inhaltlichen Bezug zum Artikel hier in der Regel nicht veröffentlicht werden.