By Manuel Müller

|

Left |

G/EFA |

S&D |

RE |

EPP |

ECR |

PfE |

ESN |

NI |

other |

| EP2024 |

46 | 53 | 136 | 77 | 188 | 78 | 84 | 25 | 33 | – |

| EP today |

46 | 53 | 136 | 75 | 188 | 79 | 85 | 27 | 31 | – |

| May 25 (B) |

49 | 40 | 130 | 76 | 179 | 79 | 100 | 35 | 23 | 9 |

| July 25 (B) |

51 | 44 | 124 | 73 | 181 | 80 | 99 | 36 | 20 | 12 |

| July 25 (D) |

52 | 44 | 126 | 75 | 181 | 84 | 101 | 37 | 20 | – |

- Baseline scenario,

as of 1 July 2025.

(Click to enlarge.)

- Dynamic scenario,

as of 1 July 2025.

(Click to enlarge.)

The mood within the von der Leyen coalition in the European Parliament has become very tense recently. The centrist alliance of the European People’s Party (EPP), the Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and the Liberals (RE), which paved the way to the election of the European Commission in autumn 2024, has never functioned particularly well. The three groups reached a basic coalition agreement known as the “Platform Cooperation Statement”. In practice, however, the EPP has increasingly been using the alternative “Venezuela majority”, i.e. an alliance with the three far-right groups ECR, PfE and ESN.

An ultimatum of sorts

Recently, even the EPP-led Commission moved towards the demands of the far right on some environmental policy issues. In response, both the S&D and RE publicly stated their disagreement and gave von der Leyen an ultimatum of sorts. By the State of the Union address in September at the latest, she must send a clear signal that the EPP and the Commission continue to support the agenda of the pro-European centre.

Should this signal fail to materialise, however, the S&D and RE will have few options for action. A vote of no confidence in the Commission requires a two-thirds majority, meaning that the S&D and RE would themselves need to join forces with the far-right groups (who, in fact, have just tabled such a vote for next week). And even if this were to happen, the next Commission President would still be proposed by the European Council, where the EPP is the largest group. An end to the pro-European alliance in the European Parliament would therefore only lead to a permanent deadlock – so we can safely assume that the EPP, S&D and RE will find a way to work together again.

Weakened von der Leyen alliance

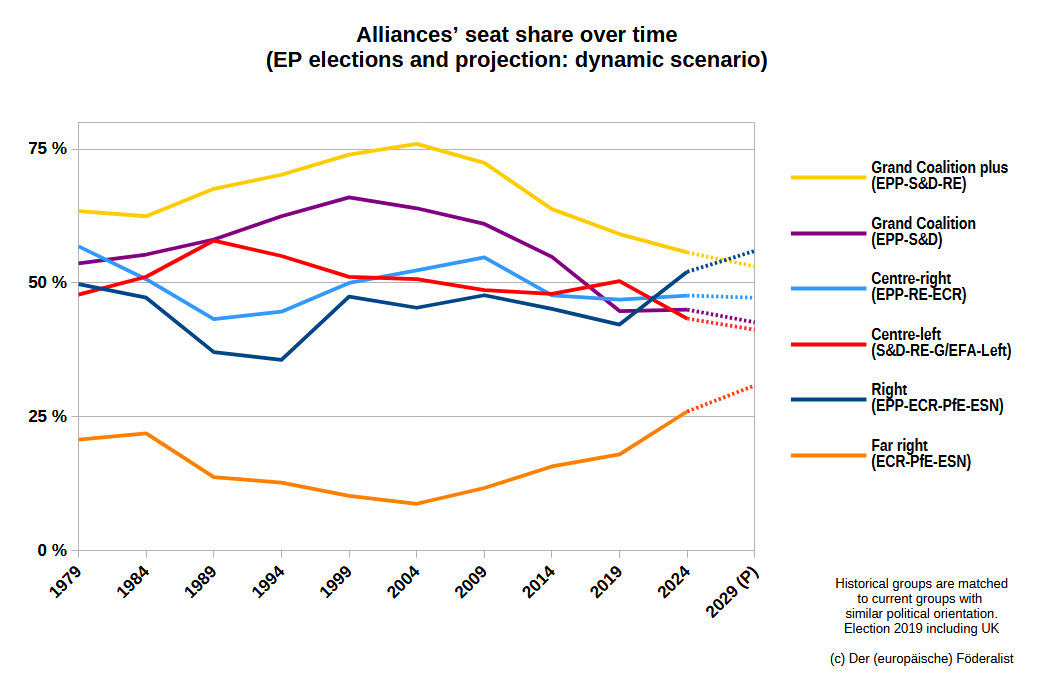

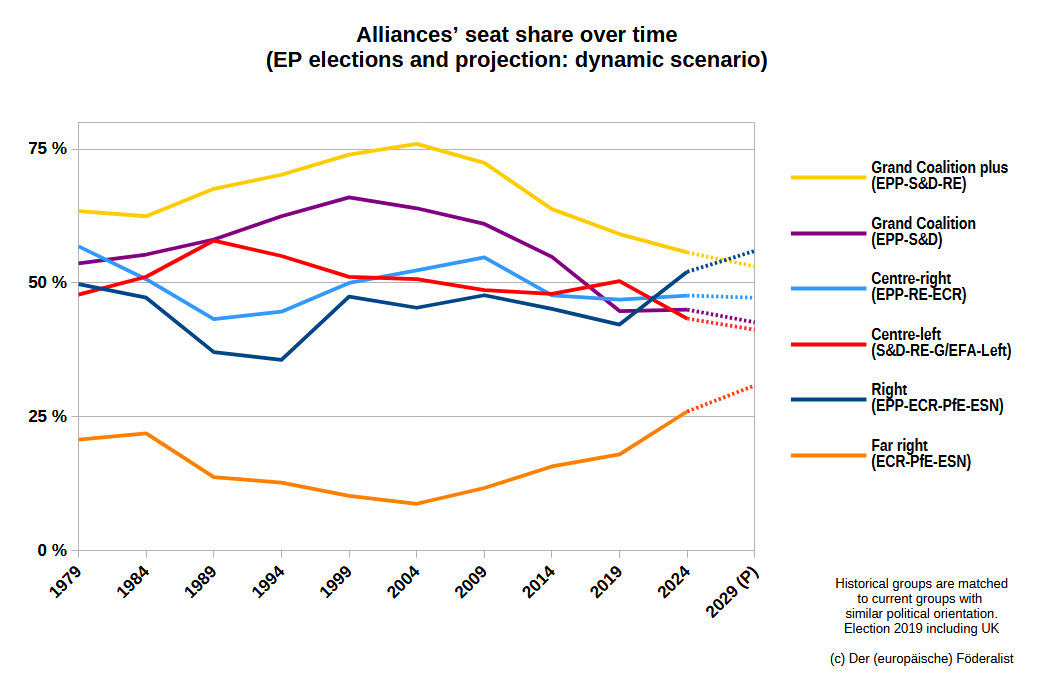

Amidst all the coalition wrangling, one thing that is always taken for granted is that the three centrist groups together have a majority in Parliament. Until the 2019 European election, the EPP and S&D had always been able to form a majority together; since then, they have needed the Liberals as a third partner. This expanded grand coalition held firm in the 2024 European election. So far, the success of the von der Leyen coalition has depended solely on the political will of its member parties, rather than on their seat numbers in the Parliament.

But for how much longer? In the seat projection, the values of the far-right bloc have risen almost continuously in recent months. The ECR, PfE and ESN climbed from a combined total of 187 seats in the June 2024 election to 196 seats in October, 200 seats in December, 211 seats in March, and 214 seats in May. In contrast, the figures for the von der Leyen coalition have continued to fall. While the EPP, S&D and RE had a total of 401 seats at the European election, this figure fell to 396 in January and then to 385 in May.

No reliable majority

In the current seat projection, the far-right bloc continues to rise, reaching 215 seats, while the centrist alliance loses ground once again. With 378 seats in the base projection, it reaches an all-time low, representing only just over half of the 720 seats in the Parliament. Taking into account that group cohesion is weaker than in national parliaments, the von der Leyen coalition would no longer have a reliable majority (unlike the “Venezuela” alliance, which stands at 396 seats).

A lot still needs to happen before the pro-European centre in the Parliament really becomes a minority. Firstly, it is likely that the EPP, S&D and RE will include new parties after the next European election that are not currently represented in Parliament. In the dynamic seat projection scenario, which takes this into account, the three groups together still hold 382 seats.

With the Greens – or the ECR?

Secondly, there are the Greens, who also belong to the pro-European centre and are generally willing to cooperate with the von der Leyen coalition. In fact, the Greens/EFA group is the biggest winner in the current projection, achieving one of their best results in this election period after a long dry spell. The EPP, S&D, RE and Greens/EFA currently have a combined total of 422 seats in the base scenario of the projection – not an overwhelming majority, but still a comfortable one.

However, the EPP would probably push for closer cooperation between the three centrist parties and the ECR instead. From the perspective of the current EPP leader Manfred Weber, at least, the ECR can apparently also be considered “pro-European” – even though this view is not supported by other EPP members, particularly the Polish PO.

Of course, the 2029 European elections are still a long way off. If recent trends continue, however, the “eternal grand coalition” could then be faced with the question of which direction it wants to expand in: whether it prefers to bring the ECR or the Greens on board as regular cooperation partners. This is unlikely to make the conflicts that already exist between the EPP, S&D and RE today any easier to resolve.

EPP: mixed balance

Taking a detailed look at the polling results of the last two months, the picture for the EPP is mixed. It has strengthened its position as the strongest national force in Germany, Spain and Estonia, and the Hungarian EPP member party Tisza’s lead over Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz (PfE) continues to grow.

On the other hand, the Polish governing party PO, led by Donald Tusk, is falling behind in the polls following the debacle in the national presidential election in June. Meanwhile, the smaller Polish EPP member, PSL, would no longer be represented in the European Parliament at all following the end of its electoral alliance with the centrist PL2050 (RE). Overall, therefore, the EPP only made slight gains, standing at 181 seats (+2 compared to May).

S&D: new all-time low

The centre-left S&D group has been the biggest loser in recent weeks. In Spain, the PSOE has been rocked by a corruption scandal and is falling behind. In Portugal, the PS continues to lose ground in the first polls since its defeat in the national parliamentary elections in May. In Romania, the PSD has also slipped further following the resignation of party leader and Prime Minister Marcel Ciolacu in May.

In Hungary, the DK, which has lost many of its voters to Tisza and has also experienced the departure of its long-standing party leader, Ferenc Gyurcsány, would now no longer be represented in the European Parliament. In total, the S&D falls back to 124 seats (–6) in the projection – a new historic low.

RE: further losses

The liberal-centrist RE group also suffers further losses in the projection. In Poland, the split from the PSL (EPP) means that PL2050 would now also fail to reach the national 5% threshold. In the Netherlands, the VVD is seeking a new direction following the collapse of the governing coalition with the far-right PVV (PfE), and ahead of the snap national parliamentary elections in November. In Bulgaria, the APS left the national governing coalition in April and would currently no longer win a seat in the European Parliament.

On the other hand, the Liberals made slight gains in Romania (where their supported candidate, Nicușor Dan, won the national presidential election in May), as well as in France and Portugal. Nevertheless, the RE falls to 73 seats (–3) in the projection, one of its weakest figures in ten years.

Greens and Left on the rise

Meanwhile, as previously mentioned, the Greens are making gains. In the Czech Republic, the G/EFA member party Piráti is benefiting from an electoral alliance recently agreed with the small Green party Zelení (EGP). In Portugal, the animal rights party PAN would now be represented in the European Parliament for the first time in a long time. The Greens are also making slight gains in Germany and Croatia, albeit only due to minimal fluctuations in the polls. Overall, the group has now 44 seats (+4) in the projection.

The Left group also saw modest increases. Due in particular to slightly improved figures for LFI in France, the Left now stands at 51 seats (+2).

ESN grows for the sixth time in a row

For far-right groups, the projection shows few changes. The ECR has gained ground in Poland and Romania, strengthening its position as the dominant national force in both countries. In Denmark, however, it has fallen back slightly due to small fluctuations in the polls. Overall, this brings the ECR to 80 seats (+1), its highest figure in this electoral term to date.

The PfE group made gains in Poland, where the far-right Konfederacja party saw significant growth following the national presidential election. The Belgian VB, on the other hand, fell back slightly, as did the PfE member parties from France and the Czech Republic, again due to minor poll fluctuations. Overall, the PfE therefore recorded a slight loss (99 seats/–1).

Within the small ESN group, the German AfD lost support but this was more than offset by the strong gains made by the Polish Konfederacja. Overall, the ESN climbed to 36 seats (+1). This is the sixth time in a row that it has gained seats in the seat projection, bringing it to almost one and a half times its level in the 2024 European election.

Non-attached and “other” parties

Among the non-attached parties, the German left-wing conservative BSW recorded slight losses. Additionally, the Czech left-wing populist Stačilo alliance and the Greek right-wing NIKI party would now both fail to meet the national thresholds. As a result, the non-attached parties together hold only 20 seats now (–3).

By contrast, the “other” parties (which are not currently represented in the European Parliament and do not belong to any European party, meaning that they cannot be clearly assigned to any political group) increase to 12 seats in the projection (+3). Some parties that had not appeared in the table for some time have now returned:

- Following the addition of former State Secretary Ingrid Coenradie (previously PVV/PfE), the Dutch right-wing party JA21 has made gains in the national polls and would now win back a seat. JA21 previously belonged to the ECR group and could rejoin it.

- In Greece, the left-wing party MéRA25 would once again just surpass the national three-percent threshold.

- The Bulgarian far-right party MECh would now also narrowly win a seat in the Parliament again. Given its Russia-friendly stance, the party is most likely to join the PfE or ESN group.

The overview

The following table breaks down the projected distribution of seats by individual national parties. The table follows the baseline scenario, in which each national party is attributed to its current parliamentary group (or to the parliamentary group of its European political party) and parties without a clear attribution are labelled as “other”.

In contrast, the dynamic scenario of the seat projection assigns each “other” party to the parliamentary group to which it is politically closest. In addition, the dynamic scenario also takes into account likely future group changes of parties that are already represented in the Parliament. In the table, the changes from the baseline to the dynamic scenario are indicated by coloured text and in the mouse-over text. The mouse-over text also lists any alternative groups that the party in question might plausibly join.

In the absence of pan-European election polls, the projection is based on an aggregation of national polls and election results from all member states. The specific data basis for each country is explained in the small print below the table. For more information on European parties and political groups in the European Parliament, click here.

|

Left |

G/EFA |

S&D |

RE |

EPP |

ECR |

PfE |

ESN |

NI |

other |

| EP2024 |

46 | 53 | 136 | 77 | 188 | 78 | 84 | 25 | 33 | – |

| EP today |

46 | 53 | 136 | 75 | 188 | 79 | 85 | 27 | 31 | – |

| May 25 (B) |

49 | 40 | 130 | 76 | 179 | 79 | 100 | 35 | 23 | 9 |

| July 25 (B) |

51 | 44 | 124 | 73 | 181 | 80 | 99 | 36 | 20 | 12 |

| July 25 (D) |

52 | 44 | 126 | 75 | 181 | 84 | 101 | 37 | 20 | – |

|

Left |

G/EFA |

S&D |

RE |

EPP |

ECR |

PfE |

ESN |

NI |

other |

| DE |

9 Linke

1 Tier

|

11 Grüne

3 Volt |

13 SPD |

3 FDP

3 FW

|

25 Union

1 Familie

1 ÖDP

|

|

|

20 AfD |

3 BSW

2 Partei

1 PdF

|

|

| FR |

9 LFI

|

4 EELV |

11 PS |

15 RE |

10 LR |

|

32 RN |

|

|

|

| IT |

10 M5S

2 SI

|

3 EV |

18 PD |

4 IV/+E |

7 FI

1 SVP |

24 FdI |

7 Lega |

|

|

|

| ES |

2 Sumar

2 Pod

1 Bildu

|

2 Sumar

1 ERC

|

18 PSOE |

1 PNV

|

23 PP |

1 SALF |

9 Vox |

|

1 Junts

|

|

| PL |

|

|

4 Lewica |

|

17 KO

|

19 PiS |

6 Konf |

7 Konf |

|

|

| RO |

|

|

7 PSD

|

4 USR

1 PMP

|

5 PNL

2 UDMR

|

14 AUR |

|

|

|

|

| NL |

1 SP

1 PvdD

|

3 GL

|

4 PvdA |

6 VVD

2 D66

|

5 CDA

|

|

8 PVV |

|

|

1 JA21

|

| BE |

3 PTB |

1 Groen

|

2 Vooruit

2 PS

|

2 MR

2 LE

|

2 CD&V

1 CSP

|

4 N-VA |

3 VB |

|

|

|

| CZ |

|

2 Piráti

|

|

|

3 STAN

1 TOP09

1 KDU-ČSL

|

3 ODS |

8 ANO

|

3 SPD |

|

|

| EL |

1 Syriza |

|

3 PASOK |

1 KD |

7 ND |

2 EL |

1 FL |

|

3 PE

2 KKE

|

1 MéRA

|

| HU |

|

|

|

|

11 TISZA

|

|

9 Fidesz |

1 MHM |

|

|

| PT |

|

1 Livre

1 PAN

|

5 PS |

2 IL |

7 AD |

|

5 Chega |

|

|

|

| SE |

2 V |

1 MP |

8 S |

1 C

|

4 M

1 KD

|

4 SD |

|

|

|

|

| AT |

|

2 Grüne |

4 SPÖ |

2 Neos |

5 ÖVP |

|

7 FPÖ |

|

|

|

| BG |

|

|

2 BSP |

2 PP

|

5 GERB

1 DB

|

|

|

3 V |

3 DPS-NN

|

1 MECh

|

| DK |

1 Enhl. |

2 SF |

4 S |

2 V

1 RV

|

2 LA

1 K

|

1 DD |

1 DF

|

|

|

|

| SK |

|

|

|

4 PS |

2 Slov

1 KDH

|

1 SaS

|

|

2 REP |

3 Smer

2 Hlas

|

|

| FI |

1 Vas |

1 Vihreät |

5 SDP |

3 Kesk

|

3 Kok

|

2 PS |

|

|

|

|

| IE |

4 SF

|

|

|

4 FF

|

4 FG |

|

|

|

|

2 SD |

| HR |

|

2 Možemo |

4 SDP |

|

5 HDZ |

|

|

|

|

1 Most

|

| LT |

|

2 DSVL |

3 LSDP |

1 LS

|

2 TS-LKD |

1 LVŽS

|

|

|

|

2 NA

|

| LV |

|

1 Prog |

|

|

1 JV

|

2 NA

1 LRA

|

2 LPV

|

|

|

1 ZZS

1 ST!

|

| SI |

|

|

1 SD |

3 GS |

4 SDS

|

|

|

|

|

1 Res

|

| EE |

|

|

1 SDE |

1 RE

1 KE |

3 Isamaa |

|

1 EKRE |

|

|

|

| CY |

1 AKEL |

|

1 DIKO

|

|

2 DISY |

1 ELAM |

|

|

|

1 ALMA

|

| LU |

|

1 Gréng |

1 LSAP |

2 DP |

2 CSV |

|

|

|

|

|

| MT |

|

|

3 PL |

|

3 PN |

|

|

|

|

|

Timeline (baseline scenario)

|

Left |

G/EFA |

S&D |

RE |

EPP |

ECR |

PfE |

ESN |

NI |

other |

| 25-07-01 |

51 |

44 |

124 |

73 |

181 |

80 |

99 |

36 |

20 |

12 |

| 25-05-19 |

49 |

40 |

130 |

76 |

179 |

79 |

100 |

35 |

23 |

9 |

| 25-03-24 |

52 |

41 |

131 |

73 |

177 |

79 |

99 |

33 |

24 |

11 |

| 25-01-27 |

48 |

43 |

130 |

81 |

185 |

77 |

93 |

29 |

24 |

10 |

| 24-12-02 |

43 |

41 |

131 |

83 |

186 |

73 |

100 |

27 |

24 |

12 |

| 24-10-07 |

44 |

41 |

136 |

79 |

186 |

74 |

96 |

26 |

29 |

9 |

| 24-08-12 |

44 |

45 |

137 |

77 |

191 |

73 |

88 |

25 |

31 |

9 |

| EP 2024 |

46 |

53 |

136 |

77 |

188 |

78 |

84 |

25 |

33 |

– |

Timeline (dynamic scenario)

|

Left |

G/EFA |

S&D |

RE |

EPP |

ECR |

PfE |

ESN |

NI |

other |

| 25-07-01 |

52 |

44 |

126 |

75 |

181 |

84 |

101 |

37 |

20 |

– |

| 25-05-19 |

49 |

40 |

132 |

78 |

179 |

82 |

101 |

36 |

23 |

– |

| 25-03-24 |

52 |

41 |

132 |

74 |

179 |

82 |

103 |

33 |

24 |

– |

| 25-01-27 |

49 |

43 |

132 |

82 |

185 |

80 |

96 |

29 |

24 |

– |

| 24-12-02 |

43 |

42 |

133 |

82 |

186 |

77 |

104 |

27 |

26 |

– |

| 24-10-07 |

46 |

41 |

137 |

79 |

187 |

77 |

97 |

26 |

30 |

– |

| 24-08-12 |

45 |

46 |

138 |

78 |

191 |

76 |

89 |

25 |

32 |

– |

| EP 2024 |

46 |

53 |

136 |

77 |

188 |

78 |

84 |

25 |

33 |

– |

The “EP 2024” line indicates the distribution of seats as of July 16, 2024, when the European Parliament was constituted following the election in June 2019.

Overviews of older seat projections from previous legislative terms can be found here (2014-2019) and here (2019-2024).

Attribution of national parties to parliamentary groups

Baseline scenario: The projection assigns parties that are already represented in the European Parliament to their current parliamentary group. National parties that are not currently represented in the European Parliament but belong to a European political party, are attributed to the parliamentary group of that party. In cases where the members of a national electoral list are expected to split up and join different political groups after the election, the projection uses the allocation that seems most plausible in each case (see below). Parties for which the allocation to a specific parliamentary group is unclear are classified as “other” in the baseline scenario.

According to the rules of procedure of the European Parliament, at least 23 MEPs from at least a quarter of the member states (i.e. 7 out of 27) are required to form a parliamentary group. Groupings that do not meet these conditions would therefore have to win over additional MEPs in order to be able to constitute themselves as a parliamentary group.

Dynamic scenario: In the dynamic scenario, all “other” parties are assigned to an already existing parliamentary group (or to the group of non-attached members). In addition, the dynamic scenario also takes into account other group changes that appear politically plausible, even if the respective parties have not yet been publicly announced them. To highlight these changes from the baseline scenario, parties that are assigned a different parliamentary group in the dynamic scenario are marked in the colour of that group. Moreover, the name of the group appears in the mouse-over text. Since the attributions in the dynamic scenario are partly based on a subjective assessment of the political orientation and strategy of the parties, they can be quite uncertain in detail. From an overall perspective, however, the dynamic scenario may be closer to the real distribution of seats after the next European election than the baseline scenario.

The full names of the political groups and of the national parties appear as mouse-over text when the mouse pointer is held still over the name in the table. In the case of “other” parties and parties that are likely to change group after the next European elections, the mouse-over text also lists the groups that the party might join. The group to which the party is assigned in the dynamic scenario is listed first.

Data source

If available, the most recent poll of voting intentions for the European Parliament is used to calculate the seat distribution for each country. In case that more than one poll has been published, the average of all polls from the two weeks preceding the most recent poll is calculated, taking into account only the most recent poll from each polling institute. The cut-off date for taking a survey into account is the last day of its fieldwork, if known, otherwise the day of its publication.

For countries where the last specific European election poll was published more than a fortnight ago or where significantly fewer polls for European than for national parliamentary elections were published in the last two weeks, the most recent available poll for the national parliamentary election or the average of all national or European parliamentary polls from the two weeks preceding the most recent available poll is used instead. For countries where there are no recent polls for parliamentary elections, polls for presidential elections may be used instead, with the presidential candidates’ polling figures assigned to their respective parties (this concerns France and Cyprus in particular). For member states for which no recent polls can be found at all, the results of the last national or European elections are used.

As a rule, the national poll results of the parties are directly projected to the total number of seats in the country. For countries where the election is held in regional constituencies without interregional proportional compensation (currently Belgium and Ireland), regional polling data is used where available. Where this is not the case, the number of seats is calculated for each constituency using the overall national polling data. National electoral thresholds are taken into account in the projection where they exist.

In Belgium, constituencies in the European election correspond to language communities, while polls are usually conducted at the regional level. The projection uses polling data from Wallonia for the French-speaking community and polling data from Flanders for the Dutch-speaking community. For the German-speaking community, it uses the result of the last European election (1 seat for CSP).

In countries where it is common for several parties to run as an electoral alliance on a common list, the projection makes a plausibility assumption about the composition of these lists. In the table, such multi-party lists are usually grouped under the name of the electoral alliance or of its best-known member party. Sometimes, however, the parties of an electoral alliance split up after the election and join different political groups in the European Parliament. In this case, the parties are listed individually and a plausibility assumption is made about the distribution of list places (usually based on the 2024 European election results). This includes the following cases: Spain: Sumar: Sumar (place 1 and 6 on the list), CatComù (2), Compromís (3), IU (4) and Más País (5); Ahora Republicas: ERC (1, 4), Bildu (2) and BNG (3); CEUS: PNV (1) and CC (2); Romania: ADU: USR (1-2, 4-5, 7-9), PMP (3) and FD (6); Netherlands: PvdA (1, 3, 5 etc.) and GL (2, 4, 6 etc.); Czechia: TOP09 (1, 3, 5 etc.) and KDU-ČSL (2, 4, 6 etc.); Hungary: DK (1-4, 6, 8), MSZP (5) and PM (7). When the election comes closer and the parties announce their candidates, the projection uses the distribution on the actual list instead. In some countries, the exact distribution of seats within an electoral alliance depends on preference votes and/or regional constituency results, so that only a plausible assumption can be made in advance. This concerns the following cases: Italy: AVS: SI (1, 3) and EV (2, 4); Poland: Konfederacja: NN (1, 3, 5 etc.), RN (2, 4, 6 etc.). In Czechia, some polls combine ODS (ECR), TOP09 and KDU-ČSL (both EPP); in these cases, two thirds of the seats are allocated to the ODS and one third to the alliance of TOP09 and KDU-ČSL. In Italy, a special rule allows minority parties to enter the Parliament with only a low number of votes, provided they form an alliance with a larger party. The projection assumes such an alliance between FI and the SVP.

Since there is no electoral threshold for European elections in Germany, parties can win a seat in the European Parliament with less than 1 per cent of the vote. Since German polling institutes do not usually report values for very small parties, the projection includes them based on their results in the last European election (3 seats each for Volt and FW, 2 seats for Partei, 1 seat each for Tierschutzpartei, ÖDP, Familienpartei, and PdF). If a small party achieves a better value in current polls than in the last European election, the poll rating is used instead. For Slovenia, the seat projection assumes that MEP Vladimir Prebilič will run for the Vesna party as in 2024; if polls show values for a hypothetical party of Prebilič’s own, these are attributed to Vesna.

The following overview lists the data source for each member state. The dates refer to the last day of the fieldwork; if this is not known, to the day of publication of the polls:

Germany: national polls, 17-30/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

France: national polls, 4-5/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Italy: national polls, 19-30/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Spain: national polls, 17-27/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Poland: national polls, 24-29/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Romania: national polls, 28-30/5/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Netherlands: national polls, 16-23/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Belgium, Dutch community: polls for the national parliamentary election in Wallonia, 23/5-3/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Belgium, French community: polls for the national parliamentary election in Flanders, 23/5-3/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Belgium, German community:

Results of the European Parliament election, 9/6/2024.

Czechia: national polls, 20-29/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Greece: national polls, 13-26/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Hungary: national polls, 17-27/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Portugal: national polls, 15/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Sweden: national polls, 13-24/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Austria: national polls, 26/5-7/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Bulgaria: national polls, 4-11/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Denmark: national polls, 19-30/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Slovakia: national polls, 8-19/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Finland: national polls, 16/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Ireland: national polls, 25/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Croatia: national polls, 25/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Lithuania: national polls, 12-18/5/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Latvia: national polls, April 2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Slovenia: national polls, 19-30/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Estonia: national polls, 13-22/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Cyprus: national polls, 11-21/3/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Luxembourg: national polls, 24/4/2024, source:

Wikipedia.

Malta: national polls, 6/6/2025, source:

Wikipedia.

Pictures: All graphs: Manuel Müller.

Correction note, 26/8/2025: In an earlier version of this article, the table showed the seat numbers of the previous (May 2025) projection for the Dutch parties. The mistake has been corrected.